Wealth in Waste: India’s Potential to Bring Textile Waste Back Into The Supply Chain

Unlocking Textile Waste Value Chains In India

This section deep dives into pre-consumer, import and domestic post-consumer waste streams. Additionally, it also highlights the end-use processes of textile waste in India

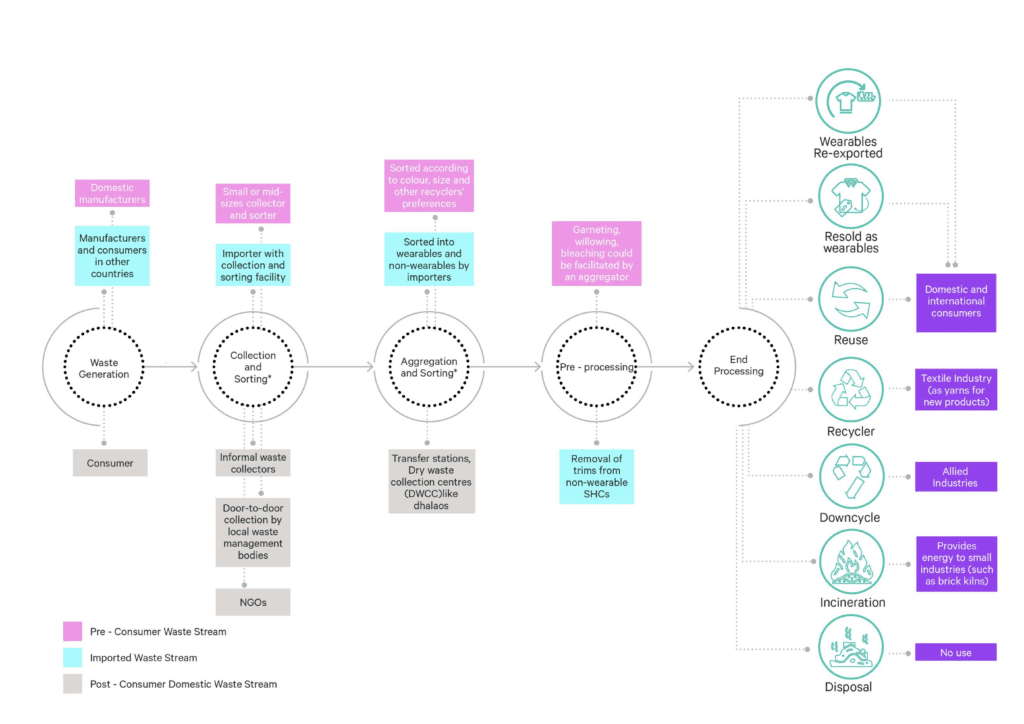

OVERVIEW OF TEXTILE WASTE VALUE CHAIN

India has a well integrated, albeit unorganised industry to deal with textile waste leading to informality and difficulties in traceability of waste

Illustration 16: Overview of textile waste value chain in India

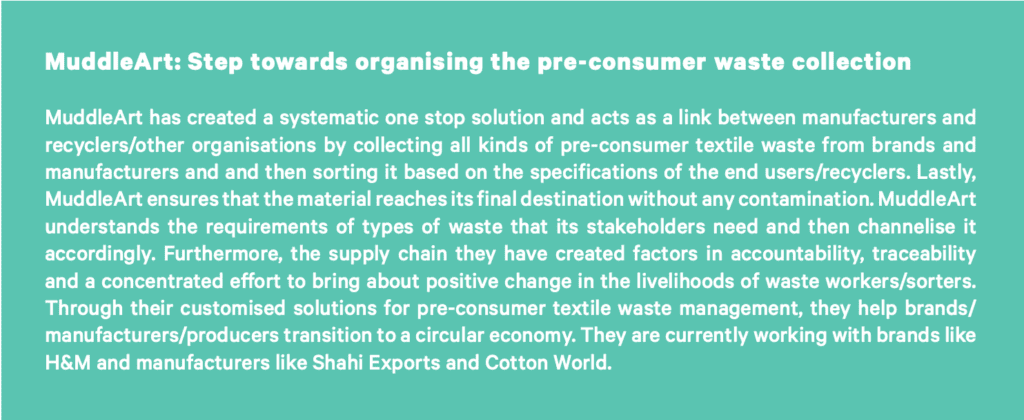

Sorting is performed manually by workers through touch and feel, based on specifications from recyclers on size, colour and composition of waste. Two to three levels of sorters and aggregators exist in the value chain and the role of the last level aggregator is not only to sort the waste but also to store the waste until adequate demand comes in. However, due to the unorganised nature of the value chain, transparency and communication on availability and requirement of waste becomes challenging, leading to leakage or under-utilisation of waste.

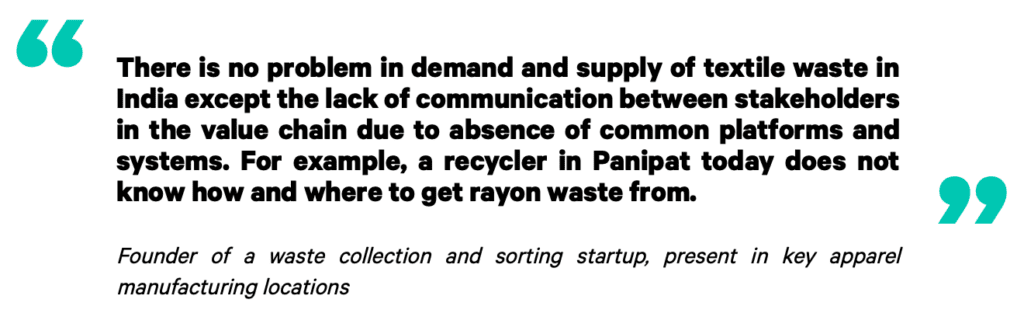

DEEP-DIVE INTO PRE-CONSUMER WASTE VALUE CHAIN

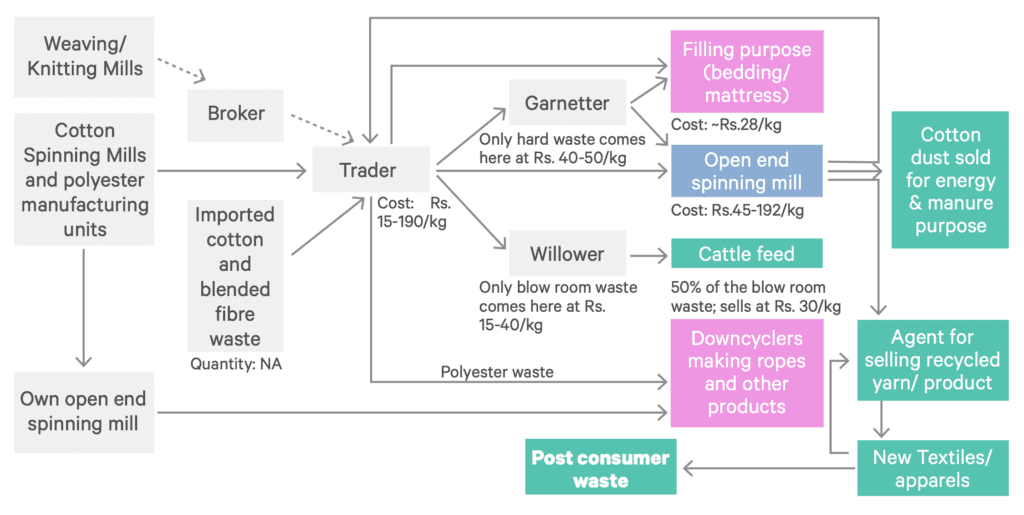

Overview Of The Value Chain: Two parallel value chains exist for pre-consumer waste in India; fibre and yarn waste generated during spinning and mill processes travel through the fibre waste value chain, while the fabric waste generated during mill and apparel production travel through the cutting waste value chain.

Illustration 17: Fibre waste value chain

Illustration 18: Cutting waste value chain

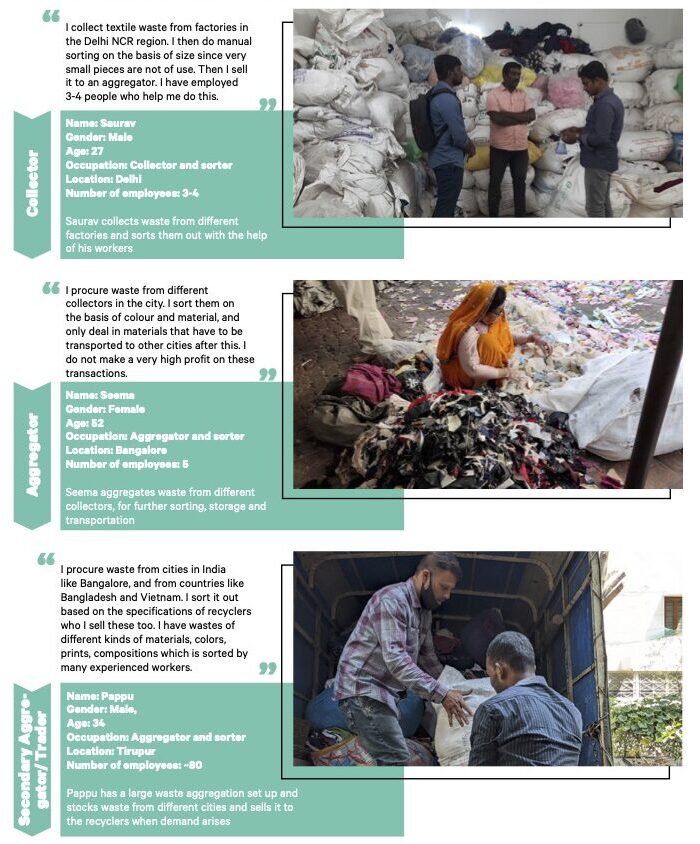

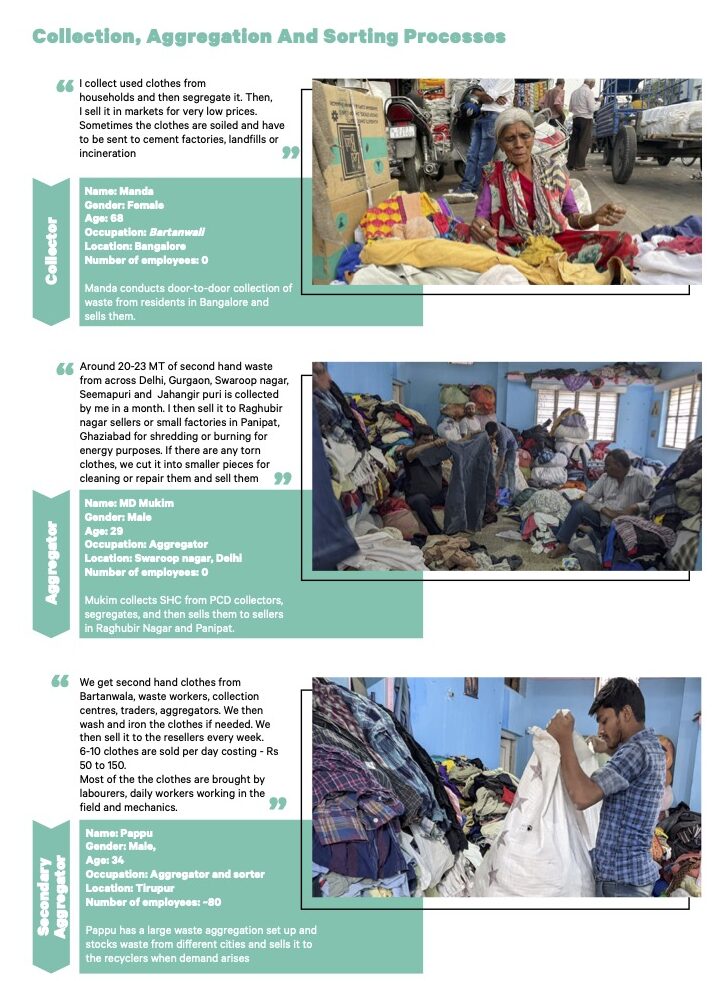

Collection, Aggregation And Sorting Processes

Waste generated in the pre-consumer waste stream is collected and aggregated by an unorganised, small-scale industry consisting of brokers, agents and other middlemen. This trade is decentralised in nature but enables management of all types of waste.

Illustration 19: Personas collecting, sorting and aggregating pre-consumer textile waste in India

Waste disposal by the manufacturers is done through a cost bidding process. This price is decided post visual inspection and is usually negotiable. In case of fibre waste, such requests are floated by manufacturers to the agents at the beginning of each month. On the other hand, for the disposal of cutting waste and fabric deadstock, orders are usually placed once the storage space in the factories is full. Both large scale spinning and apparel manufacturing units dispose off their waste every 15-20 days by truckloads. However, the quantity of such truckloads varies based on the size of collector and the availability of collection vehicles. For cutting waste, the average quantity for one shipment varies from 1000 to 10,000kgs.

Specifically for fabric deadstock and overproduced apparel, high economic incentives and a strong network of collectors and traders have ensured minimal leakage.

By following brand policies to unbrand such products, by removing size labels, logos, wash care instructions and so on, this value chain ensures incentives for all stakeholders at every point. The frequency of selling deadstock and apparel overproduction is low at the manufacturers’ end. They are usually sold once or twice a year, only after an average period of six months between original production and sales. This is to ensure that the actual value of fresh stock is realised and design imitations by market players are minimal. Depending on the specifications provided by the brands, branding components such as size labels, logos, wash care instructions and so on, are removed before selling. Fabric deadstock is mostly sold on a per kg basis (instead of a per metre basis) and is considered a low value realisation of the material at the manufacturer’s level. Apparel overproduction, on the other hand, is sold at 10% of the product’s original Maximum Retail Price (MRP), ensuring better value realisation from their perspective.

Depending on the type of waste, there could be additional processes or stakeholders involved in certain types of pre-consumer waste, before it is sent for end processing.

Fibre waste is collected and stored in a segregated manner at the factory level. On the other hand, cutting waste is not sorted by composition, size or colour at factory level and is usually sold as ‘mixed waste’. Few manufacturers, however, separate out white cuttings and bigger cut panels as they recognise the high demand for these materials and therefore are able to garner a better price. White coloured cutting waste is sold at INR 50-60 per kg (USD 0.64-0.77 per kg), while the mixed waste can be sold at a cost between INR 6-INR 35 per kg (USD 0.07-0.45 per kg) depending on the quality and market trends. However, the extent of these segregation efforts across all manufacturers in India is not effective, according to the collectors, as most of the waste is still mixed with a contamination rate up to 20%. The contaminated materials include paper, plastics, needles, tea cups, sachets, and so on. While sorting and contamination is not a concern for fibre waste, there are additional processes involved post the collection of waste. During the transaction of fibre waste, an additional layer of brokers/agents exist to ease the interaction between the manufacturer and trader by transferring supply and demand information. Post collection, willower (for blow room waste) and garneter (for yarn waste) procure the waste directly from traders/collectors. The bigger spinning establishments with their own open-end spinning mills, directly interact with willower and garneter, and buy back the processed material. On the other hand, since cutting waste is usually not processed within the manufacturing setup, apart from sorting, there are no additional processes involved in it. Unlike fibre waste, cutting waste is known to travel long distances to reach key recycling and downcycling locations from source areas. Agents/ middlemen exist in the trade to ease out transportation and transactions.

Every stakeholder in the pre-consumer waste value chain is providing a level of aggregation and sorting for the next stakeholder, while maintaining cost efficiencies.

In the pre-consumer waste stream, the requirement for sorting is highest for cutting waste and comparatively lower for fibre waste, as it is procured in a segregated manner. Sorting of cutting waste is undertaken based on the needs and specifications of the next stakeholder in the value chain. It has been observed that the first-level sorter in the value chain sorts the material only based on one parameter. At the level of the aggregator, sorting takes place on multiple parameters and as the material moves closer to the recycler/downcycler or for reuse, it reaches the desired quality. However, if the collector is a recycler as well or is interacting with the recycler directly (which has been observed in some cases), then sorting is undertaken by first-level collectors/sorters based on all possible parameters and specifications. Most small-scale collectors only sort materials based on size or in some cases colour or material, depending on the quality of waste received. These sorting parameters include material composition, colour, size, fabric construction, contamination, etc. Any traces of contamination (such as paper, needles, and so on) are mostly eliminated by the first collector/ sorter in the value chain. Such contaminated materials find their way into non-textile value chains if usable. However, most of the heavily soiled textiles are sent to landfills, forming almost 1% of pre-consumer waste. Fabric deadstock, on the other hand, is sorted by size (quantity) and thickness (quality) of the fabric. This sorting is mostly undertaken to determine and assign prices for these rolls.

Besides sorting, large aggregators also support the value chain by storing the waste till adequate demand arises.

Waste aggregation collects pre-consumer waste from both domestic and imported sources. The aggregators are in contact with the exporters in Bangladesh and Vietnam, or have their own partners in other countries who facilitate the procurement process. In this way, aggregators serve as a bridge between collectors and recyclers in India. For both cutting and fibre waste, recyclers require an adequate amount of waste of consistent quality to carry out the process. This service of providing quality and quantity of waste is offered by the aggregators who maintain waste inventory for a significant period of time for stakeholders who lack storage facilities such as recyclers and boutique owners. Aggregators often store up to 30% of the pre-consumer waste due to lack of adequate use cases of certain materials such as polyester, this waste is at risk of being landfilled or incinerated.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic:

In the pre-consumer waste stream, the closure of manufacturing units during the lockdown and the closure of local weekly markets for a long time affected both supply and demand of waste. To date, many of the traders in the waste markets do not have enough customers given low demand, due to low disposable incomes post the lockdowns. This has also led to delay in wages to the workers and layoffs.

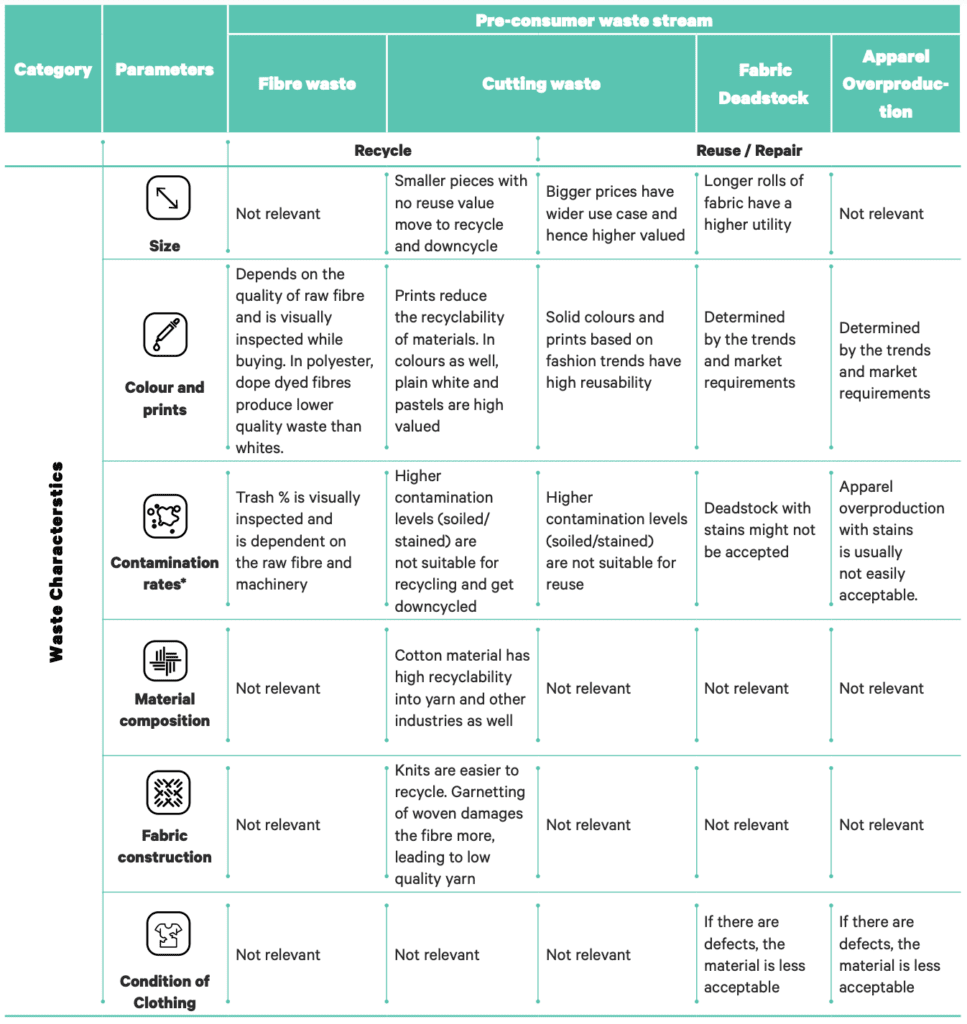

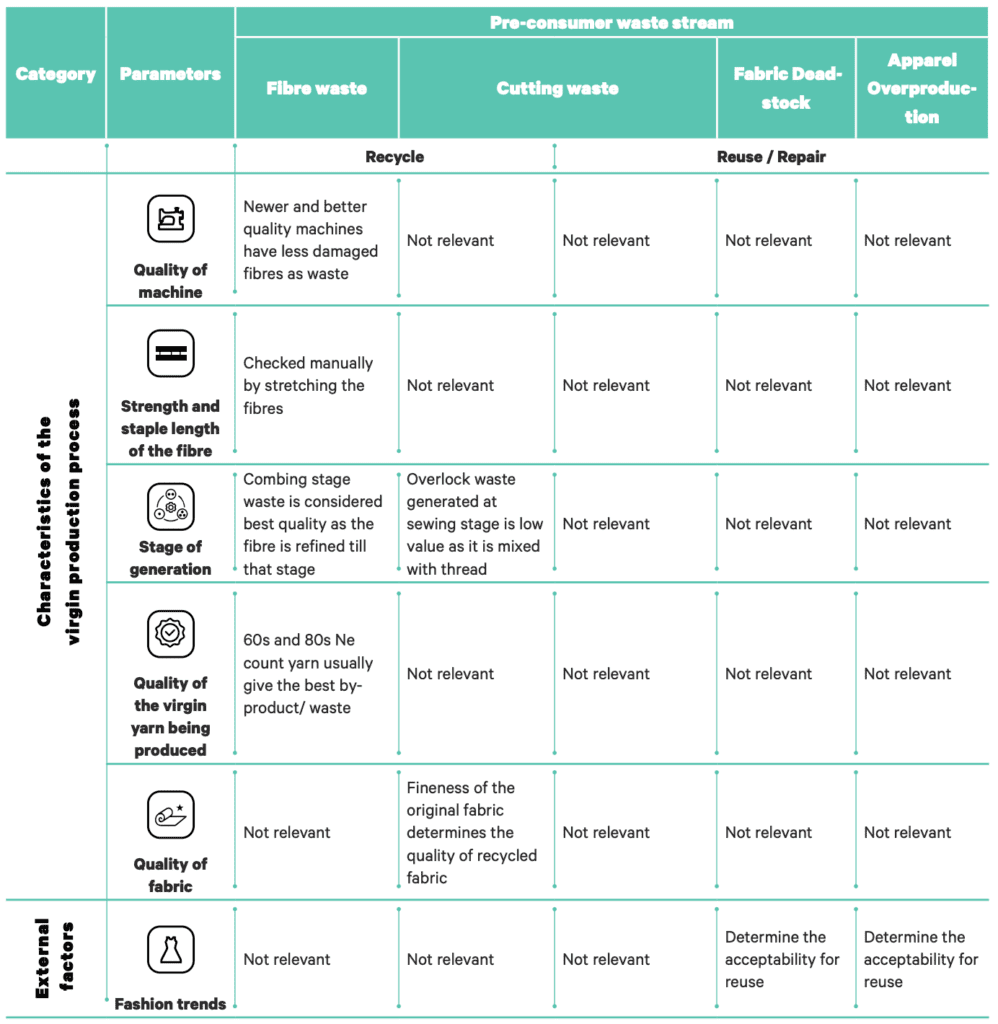

FACTORS DETERMINING THE END USE OF PRE-CONSUMER WASTE

The final level of waste sorting takes into account all the waste characteristics that determine its end use. Colour, material composition, contamination and fabric construction determine the recyclability of cutting waste. The characteristics of virgin yarn production process such as the manufacturing machine quality, strength and staple length of virgin fibre, etc., highly influence the recyclability of cotton fibre waste.

Illustration 20: Factors determining end use of pre-consumer waste

Key takeaways from the pre-consumer waste value chain:

- The value chain for pre-consumer waste stream is unorganised and informal, consisting of brokers, agents and other middlemen, who facilitate information flow between supply and demand players.

- Though informal, pre-consumer waste stream is decentralised in nature and stakeholders in the value chain prevent leakages to ensure that the waste from manufacturers is utilised within or outside the textile industry, in order to maximise returns.

- All the fibre and yarn waste generated during spinning and mill processes travel through the fibre waste value chain facilitated by brokers, traders, willowers and garnetters. On the other hand, the waste generated during mill and apparel production travels through the cutting waste value chain, facilitated by a large and wide network of collectors, sorters and aggregators between manufacturers and recyclers.

- Every stakeholder in the pre-consumer waste value chain is providing a level of aggregation and sorting for the next stakeholder, while maintaining cost efficiencies. Further, large aggregators play the role of storing the waste till adequate demand arises for end use.

- Manual sorting of cutting waste is undertaken based on the needs and specifications of the next stakeholder in the value chain. These specifications are more particular for cutting waste and comparatively lower for fibre waste, as it is already procured in a segregated manner.

- Any traces of contamination (such as paper, needles, and so on) are eliminated by the first sorter in the value chain, which could be harmful to them in some instances. Such contaminated materials also find their way into non-textile value chains if usable.

- Up to 12 quality parameters play a role in determining the end use of waste types. Most of the subtypes of spinning waste are recycled and most categories of mill waste are downcycled. RMG waste has all three applications of reuse, recycle and downcycle. Overproduction and deadstock are mostly reused.

DEEP-DIVE INTO DOMESTIC POST-CONSUMER TEXTILE WASTE VALUE CHAIN

Overview Of The Value Chain

While domestic post-consumer waste stream has many interaction points at the collection stage, there’s a lack of formal sorting and waste processing systems, making it difficult to track to prevent it from being incinerated/ landfilled.

Illustration 21: Value chain for domestic post-consumer waste

Collection, Aggregation And Sorting Processes

Illustration 22: Personas of collection, sorting and aggregation stakeholders in domestic post-consumer waste stream

1. NGOs and collection organisations:

NGOs and charitable organisations like Goonj and Clothes collection box organise community collection drives to collect wearable clothing from households. Such collections are performed door-to-door, or using drop-off boxes in local community spaces or institutions. They facilitate the transfer of clothes to those in need. NGOs and charities mostly inspect and pick up clean clothes, which are wearable or in mendable condition. These are sorted into approximately 35 categories based on utility, repairs needed, age, gender, and size. Clothing that cannot be worn is reused to make other products like cloth pads, patchworks, etc. or are disposed of to landfills.

2. Informal waste collectors:

This includes collectors from Waghri, Kathiawad and other collecting communities, commonly known as Bartanwalas or Bhandivale in India. They form an important link bartering old clothes in exchange for utensils or money from households, and selling to aggregators or in local second hand clothing markets directly. Raghubir Nagar market in Delhi is one of the biggest second hand clothing markets in India, with an overall estimated population of 25,000-30,000 Waghri community members. Each bartanwala collects 50-100 clothes daily from Delhi and the neighbouring cities.

The informal waste collectors segregate, wash and iron clothes to sell to bulk buyers or retail shops. For wearables, this segregation is performed primarily on the basis of wear and tear and quality of the garment. Dhoti and sari, on the other hand, are used in non-textile industries, as wipes and are segregated based on material composition.

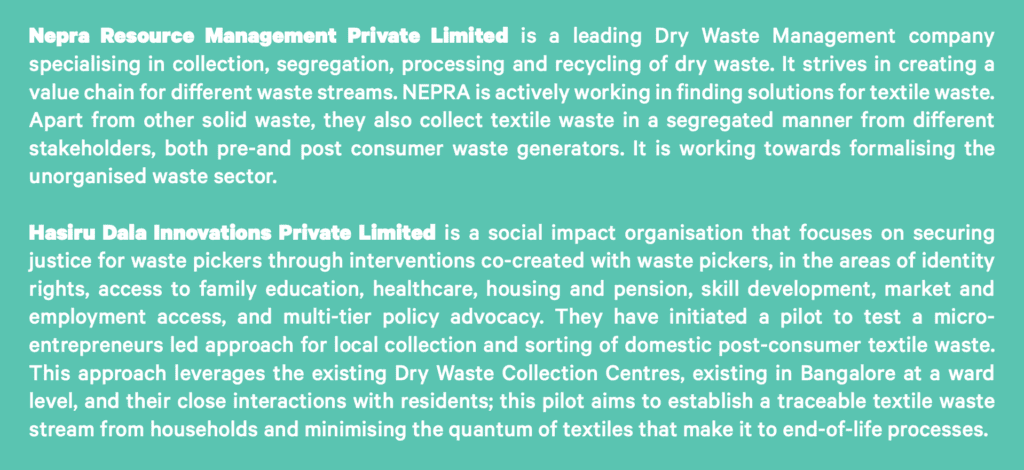

3. Municipal waste collectors:

Textile waste is also disposed through the usual household waste dustbins. This municipal solid waste collected from households is aggregated at designated centres like the Dhalaos/ transfer stations in Delhi and DWCCs (Dry Waste Collection Centres) in Bengaluru. The rag pickers in these locations collect recyclable and reusable textiles from these transfer stations. The remaining non-recyclable materials are loaded and sent to landfills or incineration for energy recovery.

The waste collected by municipal bodies in both Bangalore and Delhi, undergoes one level of manual sorting at DWCCs and Dhalaos respectively. Sorting is done on the basis of the size of the cloth and the usable materials are taken out. Out of 30 DWCCs visited in Bangalore, 23 used a manual method for sorting of garments and very few had conveyor belts. The collected waste is then sorted into wearables, which are reused or sold, and non-wearables which are compacted and sent to landfills.

4. Take back programmes by brands:

Although at a nascent stage in the country, take back programmes are brand initiatives where consumers can return old clothes back to the brand for recovering and reprocessing.

FACTORS DETERMINING END USE OF MATERIALS

Second hand clothing is expected to be in a good condition, aligned with fashion trends and size requirements for being reused. For downcycling, fewer parameters are relevant and almost all kinds of materials are used.

Illustration 23: Factors determining end use of domestic post-consumer waste

Key takeaways for domestic post-consumer waste value chain:

- Collection for domestic post-consumer waste is done through four key channels- NGOs, municipal bodies, informal waste collectors and brand take back programmes.

- Sorting of domestic post-consumer waste is dependent on the stakeholder handling the waste. The priority for each stakeholder is to identify reusable clothing for donations or resale.

- 43% of domestic post-consumer waste moving to downcycling, incineration and landfills highlight the lack of efficiency in managing this waste.

- Alignment with fashion trends, size requirements and wearable condition gives a higher return for second hand clothing being resold.

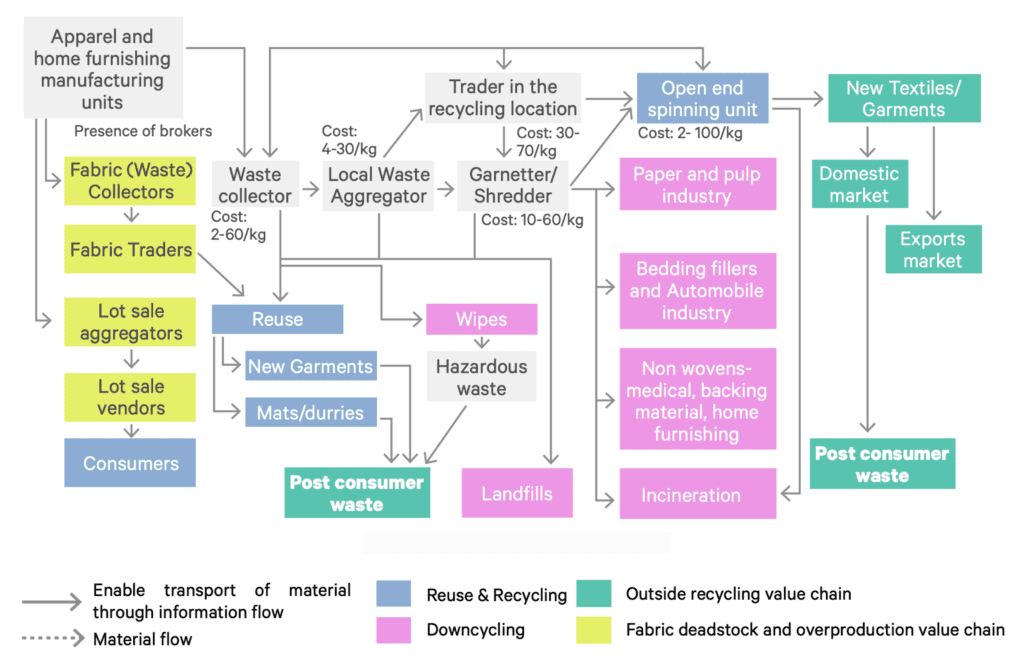

DEEP-DIVE INTO IMPORTED WASTE VALUE CHAIN

Overview Of The Value Chain

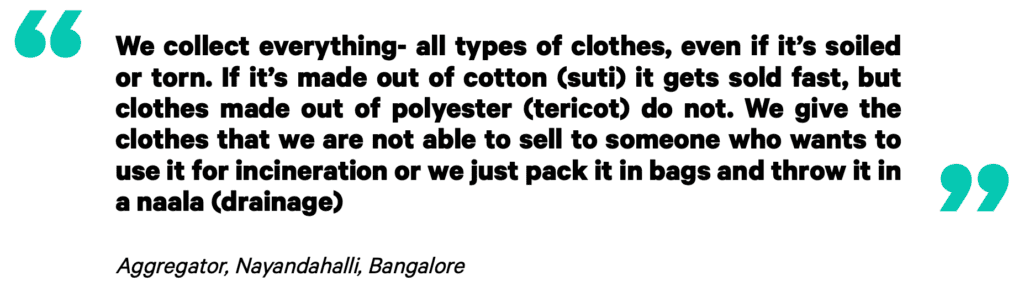

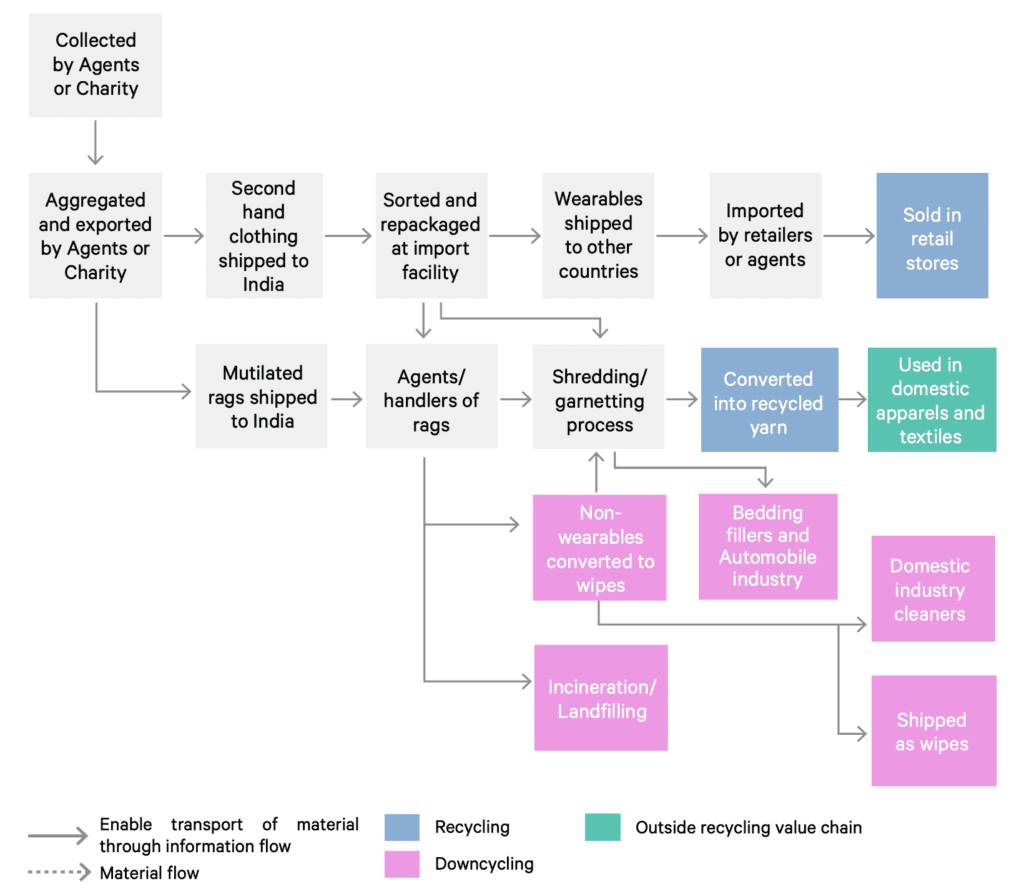

India is one of the largest importers of second hand clothing and mutilated rags, most of which is exported with or without processing. Aggregators and middlemen/women exist at every node of interaction in the value chain to smoothen out importing, sorting and re-exporting processes.

Illustration 24: Value chain for imported waste stream

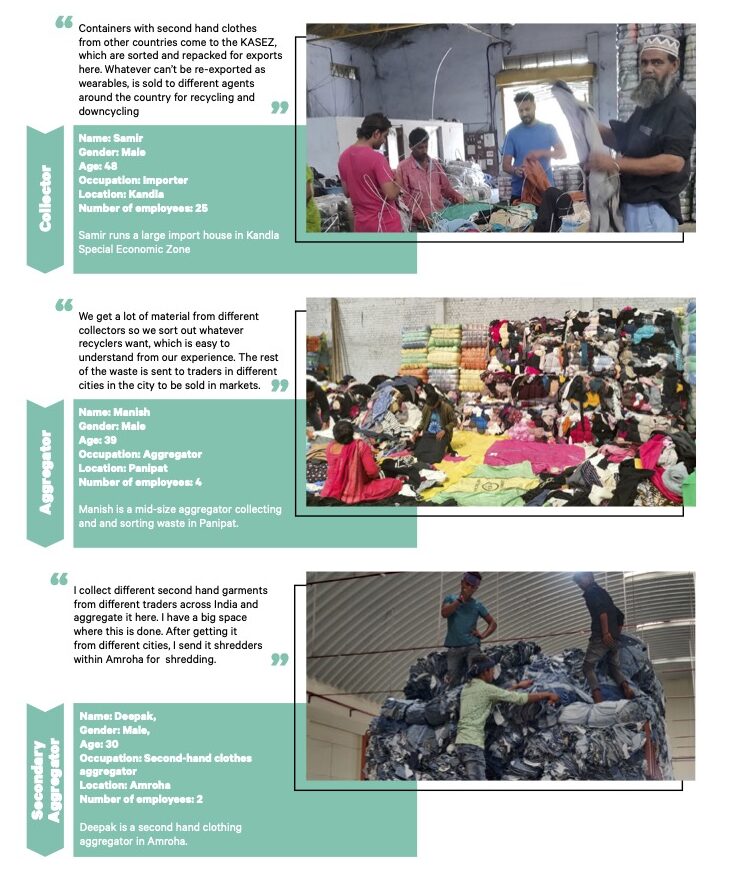

Collection, Aggregation And Sorting Processes

Illustration 25: Personas of collection, sorting and aggregation stakeholders in imported waste stream

Trade practices for imported waste varies per port and the size of the importer

In the countries exporting second hand clothing, charities collect clothing either by a door-to-door collection exercise or through community drop-off bins in different locations. These clothes are then sorted, with a small amount going to local reuse and thrift shops, the remaining is exported to India and other countries directly or via agents. In case of cutting waste/mutilated rags, the process of collection is similar to that of pre-consumer waste in India. At the importer’s end in India, orders are placed either via indentors or directly to the exporters, depending on the relationship between the importer and the exporter. On average, shipments take up to 50 days to reach India, depending on the export location. Indian ports importing textile waste have different practices as outlined below:

- Importing of second hand clothing (under code 6309) is only allowed at the Mundra port and is directly transferred to the Kandla SEZ (Special Economic Zone). Clearing agents at Mundra port are not active in this process , the customs check happens directly in the KASEZ region. Only scanning of shipment/container codes is done at the Mundra port to verify if the right containers are moving into the country.

- Customs checks for imports at Nhava Sheva port, Tughlakabad and Patli ICD (Inland Container Depots) are performed in the Tughlakabad and Patli ICD. This mandates the need for a clearing agent or an official from the importing organisation to manage the process end to end.

- Textile waste coming from Bangladesh, crosses borders via land and the customs clearance occurs at the Petrapole, 80 km from Kolkata.54

Once the material passes through the customs check, it is sent to the relevant importer for sorting, reexport and recycling processes. As per the SEZ policy (2003, 2009, 2013) issued by the Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce & Industry, items imported under HS Code 6309 second hand clothing fall under the restricted category, implying that they can only be imported at the Kandla port.55 The regulations require all importing units to re-export at least 50% of their total imports in terms of value, in order to maintain a positive net foreign exchange. The mutilated clothing that is not exported as wipes or raw material for recycling, can be sold domestically.

A sizable share of the total imported waste, while not permitted, is known to be leaked into the domestic market for repair and resale in local markets. This quantity is difficult to estimate as there are multiple points of leakages across the value chain. Additionally, due to the highly informal nature of this value chain, the study could not access stakeholders dealing with this waste and estimate its quantity.

Imported second hand clothing is sorted into 400 categories at the KASEZ, mostly for re-export purposes. The material moving into the domestic tariff area (DTA) for further processing, goes through 2-3 stakeholders before the end processor.

The first level of sorting at the second hand clothing importers’ level is undertaken according to various clothing categories such as pants, shirts, dresses, kidswear among others. While some importers use conveyor belts in the process, others use a simple trolley and bin system. Once the clothes are divided into product categories, they are further sorted into wearables and non-wearables (mutilated or stained) as well as other categories based on export requirements such as fashion trends, brands, sizes, vintage style. Garments from the USA are more in demand in African countries, as there are similarities in sizes and fashion trends. Garments from the EU mostly consist of winter clothes and pastel colours which have less relevance in these countries.

The non-wearable category is further segregated for the wipes and recycling industry. This classification is done on the basis of material composition (wipes that require cotton-rich materials) and size of the clothes. Around 35 categories of wipes have been curated by the KASEZ importers and aggregators in Gandhidham. The best quality wipes are exported for industrial cleaning purposes. The seam waste, leftover after cutting the wipes in desired size, and other non wearable waste are sent to Amroha for downcycling into fibres used for filling purposes in bedding, quilts, car seats, soft toys, etc. Sorting of material for recycling purposes is done only in Panipat, where most of this recyclable waste ends up and here as well, the first level of sorting is into wearables and non-wearables. Like the pre-consumer cutting waste, non-wearables are then sorted based on recycler’s requirements of material, colour, fabric construction, and so on.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19 pandemic has doubled the cost of importing waste, leading to closure of some import facilities in KASEZ. The onset of the pandemic significantly reduced the charity collection in exporting countries. The cost of shipping also increased along with the raw material, making procurement costly, leading to losses during importing exercises. Importers have reported shutting down operations as the imported waste value chain suffered a severe blow during the pandemic.

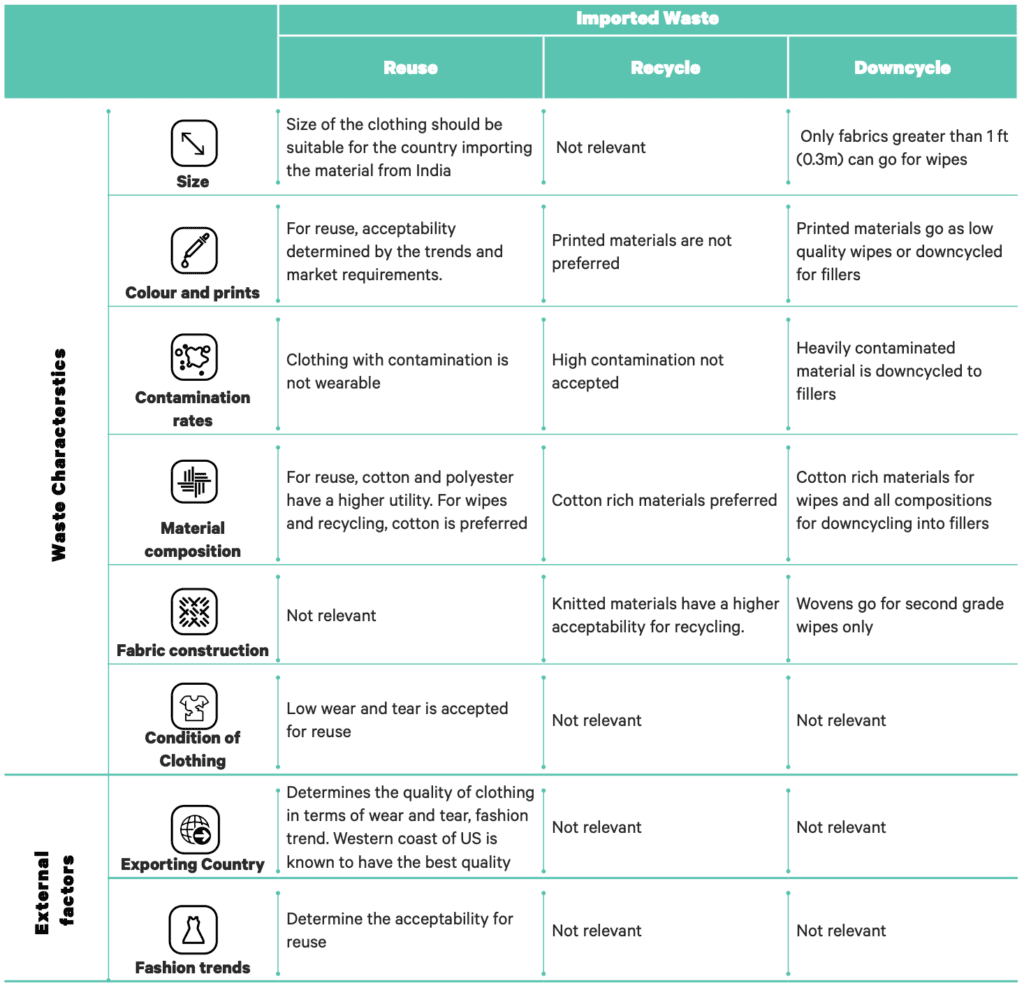

Factors Determining The End Use Of Imported Textile Waste

End of use is determined by waste characteristics such as material composition, printed fabrics, and contamination. Once these are assessed textiles are either reused , recycled and downcycled. Reuse of second hand clothing is determined by the condition of clothing (wear and tear), country it is imported from and fashion trends.

Illustration 26: Factors determining end use of imported waste

Key takeaways for imported waste value chain:

- Imported waste enters India through Kandla, Nhava Sheva, Petrapole and Patli ports. Each of the ports deal with different materials and have different trade practices. Similarly, trade practices also vary by the size of the importer and their capacities.

- Imported second hand clothing is sorted into 400 categories at the KASEZ, mostly for re-export purposes. These categories are developed based on the requirements from the importing countries and usually vary by fashion trends, size requirements and preferred material compositions.

- Non-wearable second hand clothing and mutilated rags move into India for further processing and travel through two to three stakeholders before the end processor. Wipes and recycled yarn are two most common end processes for the imported waste being processed in India.

- Parameters defining the recyclability of the material are similar to pre-consumer waste stream but for reuse, additional parameters of the exporting country becomes important.

USE CASES FOR TEXTILE WASTE: REUSE, RECYCLE AND DOWNCYCLE

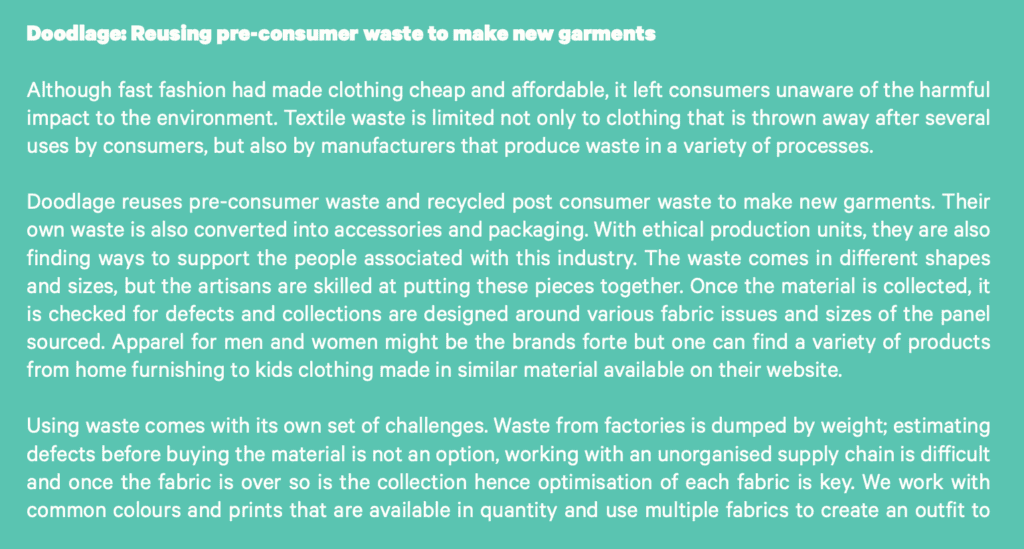

Textile waste is finding economic value by moving into textile and non-textile industries for reuse, recycling and downcycling. But there is some debate that it is not being used in the best way possible and to its fullest potential, even in the textile industry.

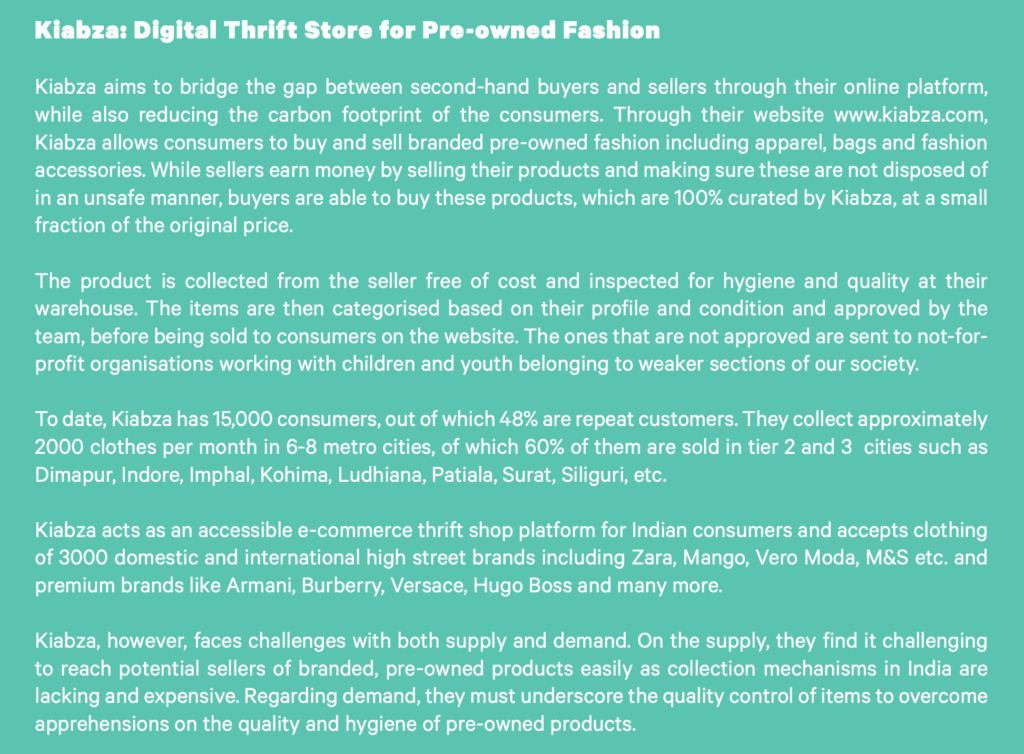

Reuse Of Textile Waste

For decades, reuse of textile waste has been a practice among domestic consumers, from hand-me-downs to purchasing it from local second hand clothing markets. A niche segment of consumers in India are also increasingly preferring second hand clothing.

Further, this segment of domestic consumers is consciously switching to more sustainable products, due to increased awareness of the impact of fashion on the environment and an increase in ongoing global conversations about circularity of textiles.56 The increase in demand for pre-owned clothes has led to the creation of innovative startups meeting the demand.

Although reuse of garments has recently been brought to the forefront, it’s had an established value chain in India for decades. Few players in the market who deal with garments or fabrics that can be reused have successfully created a large customer base over the years. However, these reuse materials were then positioned as cheaper alternatives rather than sustainable clothing.

Pre – Consumer Waste:

Following are the ways in which various materials are being reused for making new products:

- Bigger cut panels: Bigger cut panels are usually produced due to excessive or inaccurate fabric cutting. Referred to as ‘marbet/thapki’ locally, they are used to make new products that are sold in the local markets at low prices. Kidswear and undergarments are the most commonly manufactured products as they require less fabric. In parallel, ‘patti’ or the long cuttings are reused into ‘chindi durries’ and other home decor products produced on handlooms.

- Fabric rejects and deadstock: Sustainability conscious manufacturers try to limit the generation of excess fabrics, however when excess fabric is generated, they sell it either once or twice a year. Sorting of the material is done based on composition, length and quality of the fabric rolls and is sold to local tailors, reuse players or to traders for direct sales in local markets. Stakeholders who procure these fabrics make garments that are sold in local second hand clothing markets. Instances of excess fabric or rejects travelling from Bangalore to Tirupur and Erode have been found for reuse. The clothes made from these rejects and deadstock find their place in local roadside markets that are frequented by urban, semi-rural and rural populations alike. Materials like poplin for tops, rayon, twill and drill for pants and voile for lining are preferred.

Apparel overproduction generated in the factory is also sold in the domestic markets and is not regarded as waste by manufacturers.

Annual apparel overproduction amounts to about 152.5 k tons. Assuming a single t-shirt weighs around 0.4kg, there could potentially be 380 million t-shirts forming this segment.57 Taking into account the international standards of a consumer buying 13 garments every year, these garments can serve 15 million individuals in the country.58 Apparel overproduction and rejects are usually sold at significantly lower price points after removing labels, tags and logos to retain the goodwill of the company. Often overlooked, this part of the textile industry caters to a huge section of domestic consumers.

Domestic post-consumer waste:

Domestic second hand clothing also serves a large domestic need. Evidence of imported second hand clothing can also be witnessed in some of the local marketplaces.

Although a large part of the second hand clothing is handed down to younger generations and domestic help within India, some of these also make their way to local markets and thrift stores. Markets like Raghubir Nagar in Delhi and K.R Market in Bengaluru are huge second hand clothing markets that sell around 81,064 and 51,575 pieces a day respectively.59 With several godowns (warehouse) of retailers, these local markets sell all kinds of products including pants, shirts, jeans, t-shirts and tops, but the demand for sarees, dhotis and denim is higher. Since dhotis are made of 100% cotton, they are aggregated separately and sold. The collection of seasonal clothes like sweaters and blankets are primarily collected in Delhi, with smaller quantities in Bangalore. According to aggregators in Delhi, collection is at its highest during festivals like Diwali, Holi and other local festivals and lowest during winters.

Both secondary and primary sources suggest that imported second hand clothing is also sold in certain parts of Delhi, Bangalore and Mumbai. However, this was not a focus for the study and has not been studied in depth.

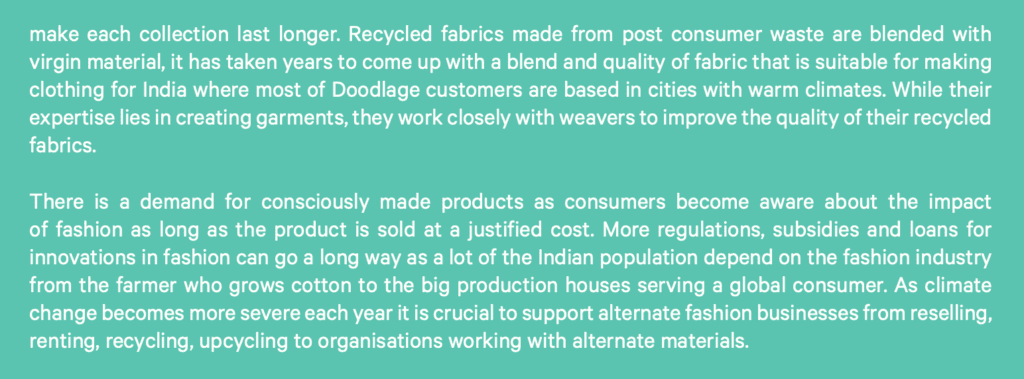

Recycling Of Textile Waste

India is one of the leaders in mechanical recycling (recycling 1900 ktons of textile waste), with high efficiency in recycling cotton and cotton blends. Influenced by industry trends, chemical and high-grade mechanical recycling technologies are also emerging in the country.

The recycled yarn produced in India is often used to make new apparels and home furnishing products for the domestic market. Open-ended recycled yarns of 0s-30s Ne count are common in the industry, with very few recyclers working with ring-spun yarns. Since the recycled yarns cut down the price of the final product by 50%, a large share, 60-90% of recycled yarn is used within the country to make products like towels, bedsheets, apparel, for the domestic market. While the remaining 10-40% are exported, they are mostly positioned as a cheaper alternative rather than a sustainable one.

Illustration 27: Processes involved in recycling in India

Downcycling Of Textile Waste

Almost 19% of waste constituting synthetics and printed materials does not return back to the textile industry, but moves to other industries such as automobile, paper and pulp, steel, and pharmaceuticals.

Illustration 28: Downcycling use cases of textile waste in non-textile industries in India

Key takeaways for end use of textile waste in India:

- End-use of textile waste can be studied on a waste value framework to understand the waste realisation

- India has an existing demand of pre-owned clothes and recycled products both in the niche, conscious citizens and the mass population who consider them a cheaper alternative to virgin materials.

- India is one of the leaders in mechanical recycling, with high efficiency in recycling cotton and cotton blends. Influenced by industry trends, newer closed-loop technologies are also emerging in the country.

- Despite the existing infrastructure, 50% of total waste is not being utilised to its best potential. 5. Blended and printed textile waste needs the highest focus as the current infrastructure and technologies are limited in their capabilities to process them.