Wealth in Waste: India’s Potential to Bring Textile Waste Back Into The Supply Chain

Becoming A Circular Sourcing Region – Key Levers

Summarises the challenges and opportunities to actualise the circularity potential of Indian textile waste

VALORISING WASTE TO FULL POTENTIAL: BRINGING WASTE BACK INTO THE TEXTILE SUPPLY CHAINS

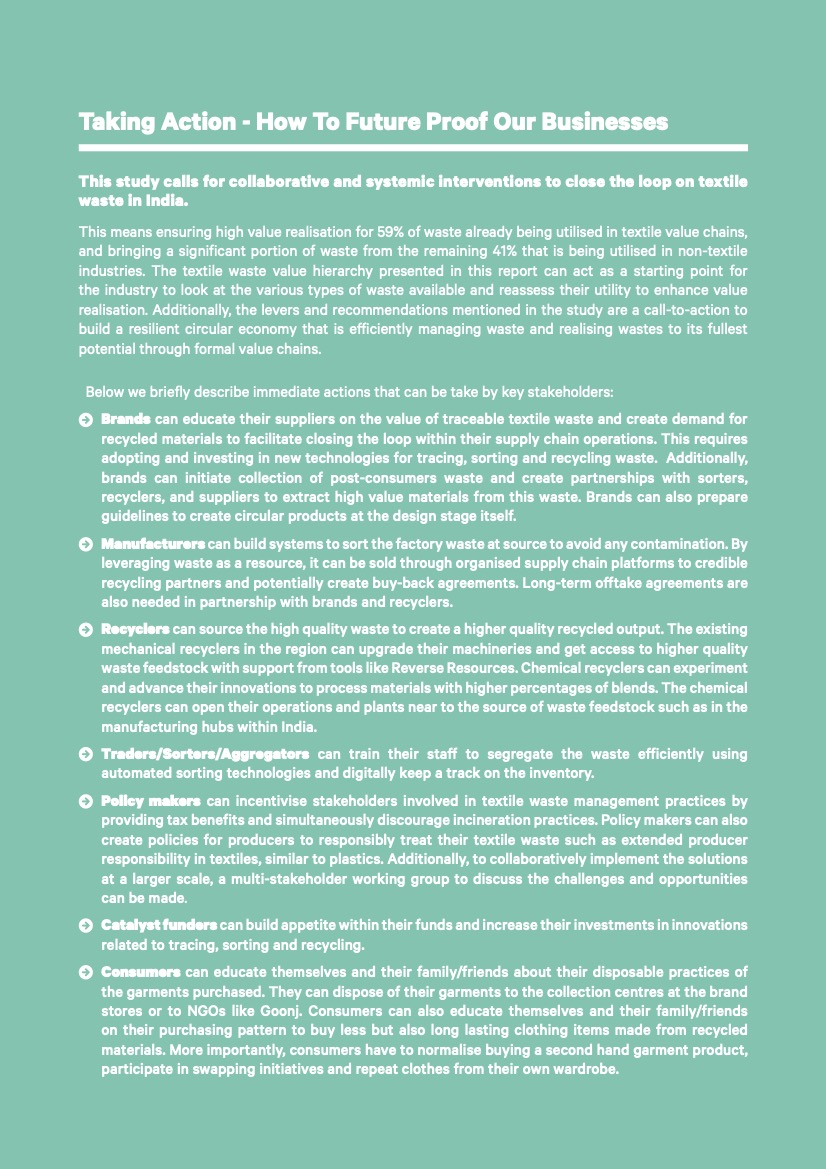

For a holistic transition from linear to circular economy, the industry needs to transform all stages of production to reduce waste generation and consumption of virgin materials, while valorising waste to its fullest potential. This transition should account for the well-being of all stakeholders across the value chain and their interests. Below we highlight the key circularity principles for the textile industry:

Illustration 33: Key principles for circularity in Textile Industry

India’s history of cotton production and the culture of reusing, remaking and redesigning garments has enabled the trade routes for textile waste and the infrastructure to process it. As compared to other countries with similar textile consumption and production patterns, the existing infrastructure and expertise makes the country strategically positioned to become a circular sourcing region. This requires minimising low value use cases and valorising waste to its highest potential. Bringing the waste back into the textile supply chains will enable use in production processes and reduce dependency on virgin materials. This study highlights tremendous opportunity in India, as value chains and processing technologies already exist.

As discussed in the previous chapters, India is the best positioned to become circular as:

- Huge quantities of waste (~7793 ktons) are generated through textile and apparel manufacturing and consumption and also imports waste, giving it unique edge over other regions

- The textile waste processing value chain is well established for reuse, high to low grade recycling and downcycling

- An informal but effective and well-integrated textile waste value chain, that also employs a large workforce

- Recycling industry in India caters to primarily natural fibres (~60% of the waste), but also has huge uptick on synthetics and covers mostly all fibres in the market

- New age technologies have an advantage to enter the market with proximity to the waste, spinning and manufacturing ecosystem

- Its a cost effective market even with the increase in the cost of living

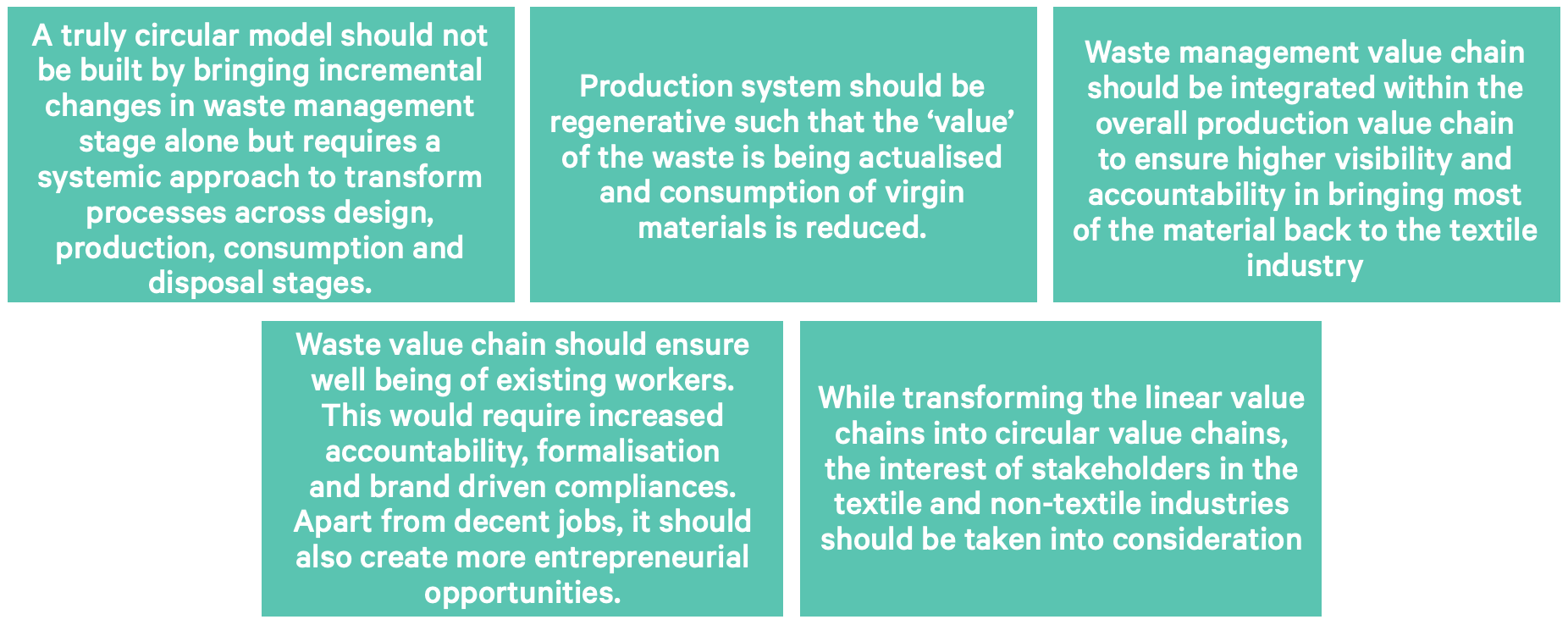

However, to realise the potential of textile waste in India, few bottlenecks need to be overcome. The study identifies four bottlenecks that the industry is currently facing and three pathways that could help it achieve circularity.

Bottlenecks To A Circular Indian Textile Industry

Illustration 34: Bottlenecks to a circular Indian textile industry

Ineffective textile waste management

Lack of standardisation and policies in terms of waste sorting and handling at every level of the value chain has led to ineffective waste management.

- Lack of data reliability and visibility of the waste value chain: Absence of segregation at source has built inconsistency and lack of visibility on waste flow. Most of the apparel manufacturers sell their cutting (RMG) waste as ‘mixed waste’ without sorting and the recycling industry depends on the collectors and sorters to sort this waste. Challenges with sorting ‘mixed waste’ exist at both manufacturers and collectors’ end. While manufacturers do not have adequate space and resources to sort this waste, accuracy of sorting as per exact fabric compositions and/or colour becomes a challenge for sorters. A similar challenge is also faced in domestic post-consumer waste streams as most of the garments received either don’t have a sorting material composition tag or the information mentioned is not accurate. In such cases, it is only the expertise of the sorters that can be used for sorting this waste. This manual process not only creates quality concerns in the recycling process but hinders the traceability of the waste. The recyclers buying the waste struggle with contamination in the waste and brands buying recycled yarns do not have reliable data and visibility on the raw material that went into recycling, which in some cases also lead to compliance issues.

- High contamination rates of manually sorted materials: The contamination rate of waste sold by manufacturers (pre-consumer waste stream) is 20%, which includes materials like needles, tea cups, sachets, harmful dyes etc, making it difficult, unsafe, and unhygienic for the sorters to handle. All these factors hinder the ability of ensuring textile waste reaches its next best use case and/or type of recycling.

- Low economic realisation of fabric deadstock, in spite of high value potential: Fabric deadstock is a highly valued waste type in the industry and is usually reused. However, full economic realisation of this waste has not materialised in the Indian ecosystem. Unlike new fabric rolls, these discarded fabric rolls are usually sold by weight rather than by length, hence not providing adequate economic returns to the manufacturers.

- Lack of standards to identify and sort waste across waste streams: While the textile waste materials travel long distances for sorting and processing to India, there are no standard processes for waste sorting. The unorganised sorting value chain mainly consists of temporary workers who have built their expertise in sorting manually through on-the-job training. Notwithstanding, chances of leakage and lack of accuracy with sorting occurs due to manual sorting processes and frequent change in workers.

- Lack of regulations for domestic post-consumer waste: In India, textile waste forms the thirdlargest share of total municipal dry waste collected followed by plastic and paper waste.62 Despite this large quantity, there is a lack of specialised policies for domestic post-consumer textile waste and is currently governed by policies designed for dry waste. Contrary to the other components of dry waste, the value of textile waste depends on the contamination rate. The lack of segregated collection from consumer results in mixing and contamination of wearable clothing, rendering it unfit for both reuse and recycling purposes. This leads to loss of economic value, while amplifying consumer apathy due to lack of understanding of this waste. According to studies, up to 86% of the domestic post-consumer waste collected by municipal bodies can be reused or reconditioned if waste management policies and logistics are strengthened.

- Rural areas are excluded from most of the waste management programmes of domestic post-consumer waste that are specifically designed for urban areas: Second hand clothing from domestic post-consumer waste streams is known to travel from urban areas to peri-urban and rural areas after they are not sold in urban areas. Online marketplace and programmes run by various government and non government organisations for recycling, reusing and waste management are mostly limited to urban areas. This, however, does not resolve the problem of domestic post-consumer waste management as a large amount of waste is generated in rural India as well.

Unorganised textile waste value chain

Unorganised and informal nature of the textile waste value chain limits the availability of waste data, leads to inefficiencies, leakage of waste, shadow supply chains and worker well-being concerns.

- Presence of unorganised value chain for all waste streams is leading to leakages of waste in the system: As per the official data on imported waste in India, 400 ktons of mutilated rags was imported in 2020 out of which, 129ktons came from Bangladesh. Since the material imported from Bangladesh is usually cotton rich, its recyclability is expected to be high. However, the study estimates that only 150 ktons of this waste was dealt within India for recycling. This clearly indicates leakage of imported mutilated rags towards low quality uses/downcycling. This could be expected for waste generated in other waste streams as well. Due to lack of data, transparency and adequate training for the traders in the value chain, leakages are occuring. The downcycling end use of this waste, not only violates the principles of circularity, but also results in economic losses for stakeholders. This leakage is mostly expected due to the unorganised nature of the value chain and lack of regulations/checks on processing of this waste.

- Procurement challenges faced by recyclers which impact the potential to valourise textile waste suitably: Presence of numerous middle men in the value chains add to the price point at every step of the supply chain, eventually making sourcing desired feedstock very expensive. This in-turn, leads to an increase in the price of high quality recycled yarns, making them expensive for the brands. Lack of background information attached to procured textile waste materials makes recycling expensive. Without background information attached to their feedstock, recyclers are at times forced to test every batch of textile waste for unwanted and banned chemicals after it is sourced. These expenses yet again add to the final price of the recycled output and make it challenging to be re-introduced into the stage of manufacturing finished garments.

- Existence of major communication gaps between industry players in all waste streams: Due to the geographical expanse of the country and largely unorganised nature of the industry, there is a communication gap between collectors, sorter/aggregators and recyclers of waste. A lot of the waste that can be used for high quality products (recycled yarns, reused for new products, etc) either lies unused or is sent for low quality use cases because the ideal use and demand of it is unknown to these traders/aggregators. This results in economic loss for the stakeholders as well as value loss of the material.

- High transport costs and non-availability of transporters: High transport charges or nonavailability of transporters poses a challenge for collectors and aggregators to ensure smooth flow of waste.

- Presence of shadow supply chains that are potentially leaking imported second-hand clothing into the Indian markets: Secondary sources have indicated that a sizable share of the total imported waste is also known to be diverted illegally into the domestic market for repair and resale as second hand clothing in local markets. This quantity was difficult to estimate due to the multiple points of leakages across the value chain.

Inefficient realisation of textile waste potential

Limitations of the current recycling technologies and the changing material compositions of the textiles have led to inefficient realisation of waste value and therefore, economic losses to the recyclers.

- Low quality of recycled yarn and mismatch in expectations between supply and demand: Most recycling units in India are not able to produce high-quality recycled yarn to the technological limitations and hence receive low prices for their products and are mostly utilised in domestic market or home textiles. While there are advanced mechanical and chemical recycling technologies available globally, large investments required to build the infrastructure are not expected to lead to desirable returns in the short-term. Aside from this business case for chemical recycling technologies are yet to be established as they are still nascent and under development. A large risk appetite is required for India to take lead in adopting these. Further, since quality is not a sole differentiator, the recycling industry is highly cost competitive which further dis-incentivises the recyclers from taking any risks as it may impact their cash flows. While a select few recyclers have found a way out of this situation, they maintain their approaches as trade secrets/patented technologies which prevents them from being scaled within the industry at-large. This situation was observed in all the three recycling hubs (Panipat, Tirupur and Amroha) of the country.

- Increase in polyester and blends is rendering a lot of material unsuitable for recycling: With everchanging fashion trends, there has been an increase in the consumption of polyester and blended materials and consequently an increase in the waste volumes of these compositions. Within preconsumer waste, a visible amount of polyester waste is observed to be lying unused at aggregator’s end or being incinerated in small soap units or brick kilns. Absence of fibre to fibre technologies for polyester and blended materials is resulting in economic losses for the importers, traders and aggregators, as there is no demand for this material.

- Domestic post-consumer waste has low recyclability due to significant wear and tear: Though a high percentage of domestic post-consumer waste is getting reused in India, about 43% of it is being incinerated and landfilled due to lack of efficient management systems and utilisation mechanisms. Recyclers interviewed across the country mentioned that they do not prefer recycling domestic postconsumer waste since the quality of waste is not suited for mechanical recycling technologies. This is because the garments in domestic post-consumer waste streams are soiled, display significant wear and tear or made with fibres that may have lost their natural strength through multiple wear and wash cycles. If this material is put through a mechanical recycling process, there may not be enough fibre strength to spin the yarn. However, the incineration and landfilling of this material is leading to a negative environmental impact.

Worker well-being and gendered division of labour

Worker well-being concerns exist across the three waste streams, particularly on the aspects of gendered division of labour and waste processing infrastructure, low wages and lack of social security in jobs, lack of safe and secure working conditions.

- Gendered Division Of Labour And Waste Processing Infrastructure: Most of the recycling and sorting set ups are owned and operated by men, while non-technical tasks are performed by women. The process of sorting textile waste during collection and recycling stages is where women and elderly are most employed. The recycling industry prefers hiring men as they require technical skills for operating the tearing, carding and spinning machines. In Ramachandrapuram/ Srirampuram market (Bangalore), men aged 18-65 own and run most of the shops selling fabric deadstock and export surplus garments. While very few women were observed running the shop, male members in their family were found to be the proprietor of the shops. In Delhi, reselling of second hand clothing occurs in markets through community based collectors and sorters. Primary resellers at these markets are mostly women. In other locations such as Amroha, Tirupur, Ludhiana, and Ahmedabad, men are observed to own collection and sorting facilities and act as traders between the sellers and buyers of textile waste while women are workers who sort waste. In DWCCs in Bangalore, out of five facilities surveyed, only two had more men than women whereas three had the same number of men and women.

- Low wages and lack of social security in jobs: Due to the informal nature of the industry, most of the workers are hired temporarily, do not get fair, consistent wages and lack social security. COVID-19 and associated lockdowns have further exacerbated the living conditions of workers as it impacted the operations of sorting and recycling set-ups. The unorganised nature of this industry stifled with competition leads to low revenues and profits of business owners, which translates to lower wages for the workers. Most of these workers are hired on a contractual basis and do not have any social security coverage. None of the workers interviewed had access to health benefits, retirement benefits, and so on. Further, some of them did not have formal savings accounts, while others were not aware of the government schemes intended to protect their welfare. Since this industry mostly employs women, the negative impact of lack of social security is much more prominent on them. The concern is even higher for certain communities involved in managing domestic post-consumer waste, for whom their occupation is also not well identified. However, a contrary situation was observed in the Kandla SEZ, where workers are considered indispensable assets due to their knowledge and skills. Despite the losses that the importers faced during COVID-19, they were found ensuring that the workers are being adequately paid.

- Lack of safe and secure working conditions: Most of the workers in the textile waste industry lack protective gear such as gloves or masks, making them prone to injuries and risk exposure to hazardous waste. During primary research, it was observed that workers in collection, sorting and recycling set-ups were not given protective gears such as gloves or masks. Further, in Amroha, sorting was performed within the recycling units without proper ventilation or lighting. The men and the women in the recycling unit were given the same number of breaks during their shift and employment, however, none of these units had sanitation facilities for women and men. The mechanical recycling process adopted in India involves garnetting and carding of the textile waste to convert it into the spinnable fibre. The fibrous dust coming out from the process is known to cause respiratory disorders such as asthma, difficulty in breathing and in some cases can lead to fatal lung diseases among the workers. The workers, however, do not have access to any protective gear and can be seen covering their noses and mouths using a cloth mask. On the other hand, in Delhi, sorting facilities in slums and encroached areas lack basic provisions such as clean washrooms, drinking water, shelter to protect workers from rain and extreme heat, etc and are also prone to fire hazards. It is important to note that the women, especially widows, seldom engage in these activities in bad working conditions due to lack of alternate livelihoods. They suffer injuries due to broken needles, glass and other harmful materials mixed in with the waste. Similar conditions can also be seen in the waste picker colonies.

So what does India need to do to bring its textile waste back to the supply chain?

Building on the existing systems and infrastructure, three key levers are required to enable India to bring this waste back.

Enabling visibility and access to waste

- Generating less or better quality waste: Circular design principles need to be built in the product design stage itself. Manufacturers should think of waste as a resource at the stage of design and production and build innovative ways of reducing and reusing them internally. In the case of postconsumer, recovering waste directly from consumers might lead to an increase in reuse and reduce the waste moving to landfills.

- Sorting and segregation of pre-consumer waste at factory floor: Contamination of textile waste with non-textile materials needs to be avoided. This could in turn not only provide hygienic and safe waste for sorters to work with, but also avoid any deterioration in waste quality due to staining and soiling. A collaborative effort between manufacturers, recyclers and collectors/sorters, to build an efficient system with minimal disruptions is the way forward. There’s a need for specifications by brands or manufacturers to provide non-textile waste bins at factory floors, and educate the factory workers on improved waste handling and textile sorting processes.

- Sorting and segregation on post-consumer waste: Post-consumer waste is challenging due to the disrupters and while they still need manual segregation, sorting technologies can make this process transparent and traceable. Sorting technologies seem to be the way forward to provide the accuracy on material composition required for high-end recycling. While the technologies for sorting are in the nascent stages and the accuracy and business models are still being established, industry testing is the way forward to improve these metrics. They have a potential to increase accuracy and reduce time put in by the workers, however, benefits of this additional cost still need to be validated. In the near-term, pilots of globally available technologies can be done and at scale implementation can be attempted if the results are positive.

- Real time waste mapping and supply chain transparency: Real-time digital platforms can improve communication between supply and demand stakeholders, while enabling maximum and right utilisation of waste. Though the challenge of lack of communication is most evident for pre-consumer waste streams, a customised digital platform that provides a detailed view of waste quality and its market demand can serve all the waste streams. Technology can also support importers in predicting the flow of imports/waste generation in exporting countries, and forecast demand from the recycling industry. Technologies such as Textile Genesis, Apparel Magic, ChainPoint63 and others may help in mapping the waste throughout the value chain and track waste leaking out of the system, ensuring higher circularity in the industry. Alongside, it could help in mapping the stakeholders dealing with waste and provide adequate micro-level visibility to waste management on ground. Success of this technology is dependent on its adoption by all stakeholders in the industry making this a long-term solution as a significant amount of investments and capacity building towards it would be required.

Harnessing recycling potential of India

- Upgradation of existing mechanical recycling facilities: Advanced mechanical recycling technologies exist globally and can yield higher quality of recycled yarns. Investments and brand buy-in are required to pilot and implement these technologies in India. Once these technologies are established and adequate return on investment is achieved, new recycling/waste processing hubs can be developed which would significantly lower the cost of transportation, resulting in economic benefits for all stakeholders. Government can play an active role in boosting these new economic zones.

- Investments in innovative chemical and mechanical recycling technologies: Dedicated technologies for other material compositions beyond cotton, such as polyester, spandex, acrylic and high quality wool needs the focus of the ecosystem in the mid-term while technologies that can accept newer variety of materials (bamboo, hemp, modal etc.) and blends of different proportions at different quality levels can be built over the long-term. These technologies can be either mechanical, chemical or a mix of both but cost efficiency and environment friendliness need to be ensured as key principles. Alongside, R&D on building further chemical recycling for materials that cannot be mechanically recycled should be the focus of the industry in the long-term. R&D, piloting and investments towards these technologies can be collaboratively supported by brands, innovation platforms, philanthropists and government bodies.

- Re-evaluate and standardise minimum prices offered by brands and manufacturers for recycled yarns. Along with the efforts involved in collecting, sorting, transporting and processing this waste, the textile waste market in India is also subject to volatile import and raw cotton prices. These efforts and volatilities need to be dynamically accounted for while fixing prices for the recycled yarn. Alongside, a share of unused waste also exists that is adding to the cost of the traders that needs to be accounted for. Incentivisation, setting a base minimum prices as well as long-term partnerships between the buyers of recycler yarns and recyclers, can result in economic uplift of recyclers, stabilised demand and supply.

Establishing systems, infrastructure and regulations for textile waste management

1. Formalise textile waste value chain, ensuring worker well-being and high value returns for all stakeholders

- Ensuring legal registrations (such as GST) for the waste collectors/sorters/ traders/aggregators and providing them incentives to be a part of the formal value chain.

- Providing adequate training support on sorting processes, safety measures, etc to the waste workers to build their capacities.

- Providing dedicated, hygienic infrastructure such as covered and ventilated sorting spaces, washrooms, drinking water, etc to the workers working in slum or encroached areas.

- Compliances with respect to fair wages, working conditions, social security measures such as pensions, insurance and standard working processes need to be built in.

- GRS certifications can be encouraged among the stakeholders as it ensures reliable information for recyclers and brands and also allows the waste traders to get premium prices for their waste.

- Building a centralised database with all waste collectors/sorters/traders/aggregators could also help in formalising the value chain.

Brands along with manufacturers and recyclers can support development of certain compliance and certifications for the waste traders. These compliances can be scaled by both manufacturers and recyclers by incentivising traders to adopt them. However, all such efforts need to keep the betterment of workers and waste management at the centre, by not levying additional costs for the small stakeholders in the value chain.

2. Material identification and sorting standards: In the long-term, the textile waste industry needs standards on identifying, sorting and handling textile waste, to comprehend their end-use easily, across the world. These could be similar to the standards set out for plastic waste that depict their level of recyclability. The standards can be developed taking into account the following principles: 1) Existing practices and knowledge of the collectors and sorters should be accounted for 2) Adequate capacity building of existing workers should be done to adapt them to new standards and ensure their presence in the value chain 3) Standards should be global in nature to ensure similar understanding among all domestic and global stakeholders 4) Standards will have to be inculcated in the manufacturing process as well.

3. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) for textile waste: An Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)64 policy, similar to that of plastic packaging, could bring in economic incentives for all stakeholders in all waste streams as well as enable traceability and transparency. While the Indian informal ecosystem has been working towards maximising the utilisation of this waste, the changing consumption and disposal patterns require better tracking and accounting of this waste, while also ensuring the well-being of workers in the sector. France was the first country to adopt an EPR policy specifically for the textile industry in 2009.65 The country has drafted and implemented a legal framework that requires producers to assume responsibility and cost of collection, treatment and recycling of their end-of-use products such as clothing, linen and shoes. The producers are mandated to do so either by ‘financially contributing to an accredited Producer Responsibility Organisation (PRO), or by creating an individual take-back programme approved by French public authorities’.66 If such a policy is implemented in India, it would lead to systematic collection of domestic postconsumer waste, prevent it from getting soiled through better segregation practices and increase the reusability and recyclability of the waste.

Consumer education on post-consumer waste collection: Consumers are an important part of the domestic post-consumer waste supply chain and hence building their awareness on the types of domestic post-consumer waste (wearable, non-wearable, discarded) and the appropriate channels for discarding each of them is needed. Additionally, upon design and implementation of policies on segregation, there is a need for large-scale awareness campaigns on the kind of bins and frequency of collection of this waste. Consumer Behaviour Change Campaigns (BCC) can also be undertaken to change consumption and disposal patterns such as swapping of clothes, thrift, rental, repair stores.

Saahas Zero Waste : Creating value out of domestic post-consumer textile waste in Bangalore

Textile Waste post-consumed currently has no viable solutions which leads to its contamination and being dumped in the landfills or incinerated. The NGO’s, Pheriwala or bartanwala are some of the stakeholders in the supply chain who collect such garments but not all collected are utilised. Predominantly, the fast fashion garments in unused and good condition are dumped,unused, contaminated or burnt. An ideal solution to this is setting up collection and centralised sorting mechanisms for domestic postconsumer textile waste.

Saahas Zero Waste (SZW) is one such organisation working towards managing municipal solid waste in India for nearly a decade. Specifically for textile waste, SZW organises collection across Bangalore through RWAs, residential complexes, commercial spaces like tech parks. They collect an average of 5 MT in 10-15 days.

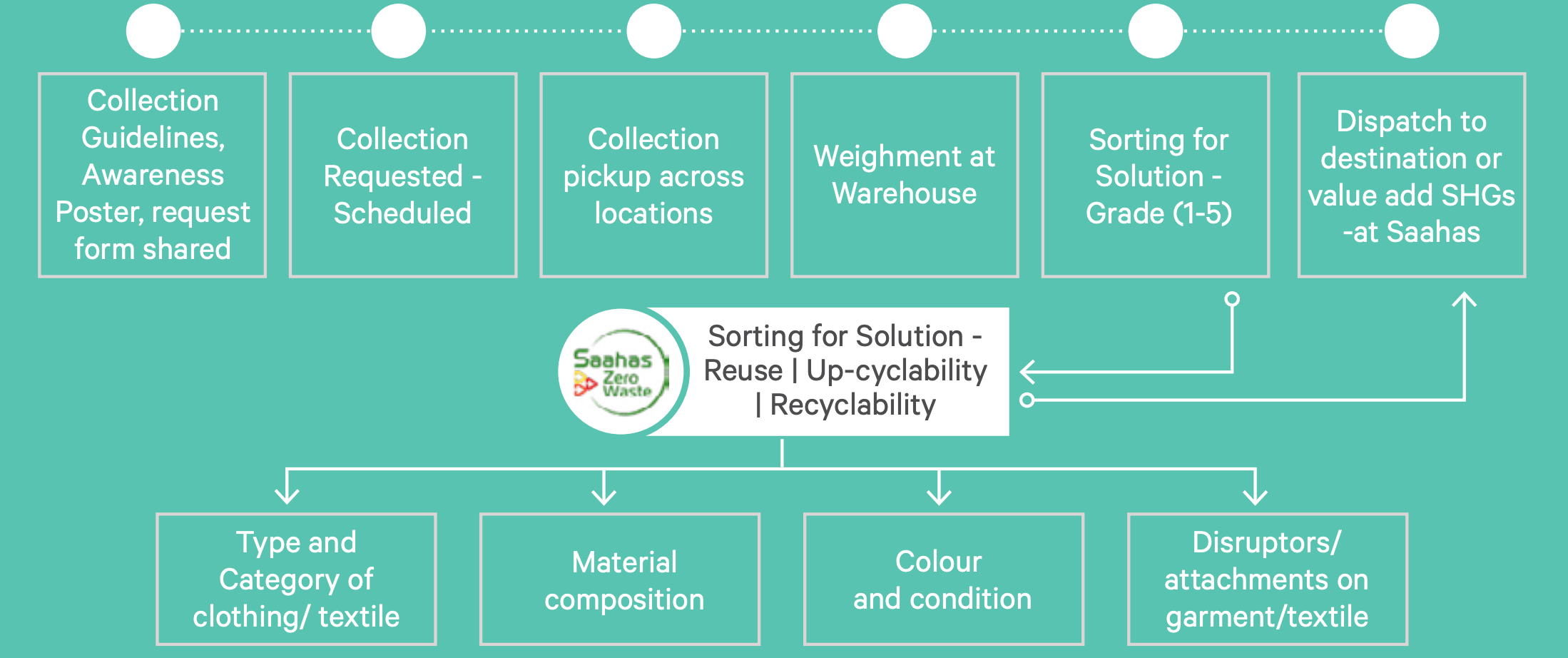

In terms of their processes:

Awareness and communications are done 10 days before the collection drive. A live form is sent across various channels which enables anyone to register and raise collection requests. The data from request forms are analysed and the collection is scheduled using predefined algorithms. The collected material is sent to the SZW facility and weighed before it is sent for further processing. The collected textile waste is sorted in Grade 1 to 5 depnding on defined parameters including quality, condition and end use. During the sorting process, the data mapped and recorded in the internal data management system for further analysis.

The sorting of such material is time and labour intesive, however the process can be optimised by deep study and profiling of the waste materials and technology intervention.

Illustration 37: Collection and Centralised Sorting Mechanism of SZW for domestic post-consumer in Bangalore

SZW has also been actively engaging on aspects of social welfare of workers. In 2019, SZW first set out a social inclusion project. Since then SZW has been working with different partners to facilitate the transition of Informal Waste Worker to a formal waste ecosystem.

SZW has recently initiated a pilot with Circular Apparel Innovation Factory (CAIF) to test a microentrepreneurship led approach for local collection and sorting of pre-consumer textile waste. This pilot aims to establish traceable textile waste through a self-sustaining entrepreneurship model focusing on creating green jobs for waste workers which ensures environmental and social compliance.