Sorting For Circularity Europe: An Evaluation And Commercial Assessment Of Textile Waste Across Europe

Introduction

Fibre-to-fibre textile recycling commitments and policies are continuously increasing, as one of the key strategic components propelling businesses to support the transition towards a circular fashion industry. Brands and manufacturers have made strong commitments to increase cyclability and use of secondary raw materials, such as the Global Fashion Agenda 2020 Circularity Commitments,12 Ellen MacArthur’s Make Fashion Circular Commitments and the Jeans Redesign Guidelines13 or WRAPs Textiles 2030.14 Commitments have been accompanied by substantial increases in the number of facilities certified to operate under recycled content standards, resulting in a nine fold increase between 2014 and 2019 of certified facilities by the Recycled Claim Standard (RCS).15 The European Commission is also expected to drive further change in the EU policy environment in the coming years, as the EU Textiles Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles unfolds.16

In turn, these developments are expected to drive an increased demand for post-consumer textiles collection, sorting and recycling operations across the EU. Whilst there has been a surge in innovation in recycling technologies that can handle a variety of different textile materials, significant investment is still required to enable fibre-to-fibre recycling to operate at scale. A study by McKinsey (2022) estimates that investments in the order of 6 to 7 billion euros may be needed by 2030 to scale the industry to be able to recycle 18 to 26% of gross textile waste in Europe.17 The investment needs are not only relevant for chemical and mechanical recycling technologies but also across the entire value chain, including sustaining and further developing pre-processing operations such as hardware removal and sorting in Europe.

In order to holistically inform any future investments, there is a need to understand both the characteristics of post-consumer textiles available in the European market as well as the business case for monetisation through recycling. The Sorting for Circularity Europe Project was created to address this knowledge gap, exploring these materials in depth. The Project is aimed at analysing types of waste being generated, quantities available as feedstock for recycling, and the ability to channel textile waste as feedstock for those with innovative solutions. This report is key as it is the first to provide powerful information on which informed decisions can be made for further investment, policy developments and next steps towards circularity.

OVERVIEW OF TEXTILE FLOWS ACROSS EUROPE

Between 2005 and 2019 the European textile and apparel market grew by 15%. This means that each EU citizen consumed on average 12.4 kgs of textiles in 2019 —of which 10.0 kg was clothing.18 Thus, approximately 5.4 million tonnes of new clothing and household textiles were placed on the market across the EU-27 in 201919. While this growth represents an increase in the amount of textiles consumed, the amount spent by consumers on clothing and household textiles has merely risen 1% since the beginning of the century20, meaning that we are purchasing more textiles for approximately the same amount of money.

On average, 38% of the textiles placed on the market each year are collected separately when the consumer no longer wants them. This is based on the average of the countries in focus for this Project and in line with the European average21, with a lower average of 12% for Spain22 and a higher one of 60% for Germany23. Textiles are mostly collected via bring banks, usually complemented with indoor collection systems at first- or second-hand retail stores, except for the UK where the predominant mode of collection is via charity shops. With a few exceptions, separate collection systems are primarily in place for the collection of clothing for reuse on global second-hand markets and the majority of the textiles collected separately is reused. In the focus countries of this Project, 55% is sold as rewearable textiles, with the purpose of reusability, which aligns with other publications in the European landscape.24

However, at collection points, citizens also dispose of clothing and textiles that are not rewearable in its current state. This means a significant share of those are diverted into other applications with lower environmental and economic benefits. These post-consumer textiles (PCT) are usually referred to as non-rewearable , either because of their unsuitability for the second-hand market (extensive use or damage, lack of quality, cleanliness) or due to the market saturation that lower quality second-hand clothing currently faces on global markets.25

Separate collection of textiles across Europe is projected to change and increase significantly after 2025. The 2018 revision of the EU Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC) requires all EU Member States to ensure that systems are in place for the separate collection of discarded textiles by January 1st, 2025.26 For countries where there are well-established and well-used commercial and charitable collection systems, the main change will be an increased collection of the non-rewearable fraction. In countries with less established systems there is likely to be an increase in collection of both rewearable and non-rewearable textiles. Increasing separate collection quantities will depend on how active Member State governments are in establishing collection systems, the degree to which they set targets for collection and the resources they use for increasing awareness amongst citizens. As a benchmark, the countries and regions that have been most active in increasing textile collection to date – France, Belgium (specifically the province of Flanders) and the Netherlands – observed increases in the order of 180 to 220 grams per capita per year. This has been mainly due to proactive public initiatives to increase collection rates through either Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), soft target setting and citizen awareness raising campaigns. This could mean for example that in Spain collection rates could go from the 12% mentioned above to roughly 24.6% by 2030.27 Additionally, not only the quantities for all separate collected textiles is foreseen to increase, but the trend shows that the quality of the textiles collected is also decreasing amongst others. This is due to increasing pollution of collected textiles with household waste, extensive use or damage, decreasing material quality, the market saturation that second-hand clothing is currently facing or even due to the emergence and growth of customer-to-customer (C2C) platforms.28 29 All of this will lead to an increase in non-rewearables present in PCT.

EUROPEAN UNION UPCOMING LEGISLATION

The Waste Framework Directive aims to protect environmental and human health by preventing and reducing waste. It sets basic concepts and definitions related to waste management, recycling, and recovery, and specifically sets a waste hierarchy for the Member States within the European Union. It defines when waste ceases to be waste and when waste can become a secondary raw material.

The Directive’s 2023 revision focuses on introducing and implementing:

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) makes producers operationally and financially responsible for the end-of-use phase of the products they put on the market, and aims to introduce economic incentives such as eco-modulation fees.

Polluter Pays Principle (PPP) places the responsibility of covering costs related to environmental damages caused by polluter’s actions or operations. A recent EU Commission study indicated poor implementation of the PPP within the textiles sector, the revision hopes to improve the implementation and prevent pollution through schemes such as EPR and separate collection.

Separate collection of waste mandates Member States to separately collect waste produced by households by 2025. The upcoming 2023 revision aims to set a mandatory step to prepare textile waste for reuse.

The increased volumes of textiles will need to be sorted and prepared for reuse or recycling. The textile sorting system today heavily relies on manual processes that effectively serve the reuse market, which is currently the main financial driver for these activities, and will remain so for the foreseeable future. As such, manual sorting is likely to remain the first step for sorting any PCT with rewearable content. However, manual sorting is not the optimal solution for recycling, especially for high quality mechanical and chemical recycling which requires identification of specific fibre types. To feed such recycling markets, manual sorting is likely to be followed by automated, or semi-automated, sorting of the non-rewearable fraction by fibre type and colour. A better understanding of the typical material composition of non-rewearable textiles is currently needed to guide investments into appropriate recycling facilities that are tailored to the fibre composition and volume of future flows of textile waste.

Aim and Objectives

The Sorting for Circularity Europe project (the Project) aims to create greater harmonisation between the sorting and the recycling industry to ensure that increasing amounts of collected low value textiles can be diverted away from their less circular destinations, like downcycling, the wipers industry and incineration, to recycling solutions. The Project has two phases; phase one aims to assess low value post-consumer textiles in the following six countries: Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, the United Kingdom and Poland (referred to as focus countries). Phase 2 aims to support digital platforms that match supply and demand by connecting sorters and recyclers through waste mapping and match-making capabilities, to ultimately facilitate the recycling of textiles across Europe and Global regions in a transparent and open-source manner. Overall, the research outcomes of this Project can enable and inform investments in the sorting, pre-processing and recycling infrastructure needed to commercialise textiles currently considered of low value in the market.

This report showcases Phase 1 results and briefly discusses key players operating in Phase 2.

The Fibersort Project

The Fibersort Project was an Interegg funded project, led by Circle Economy and involved partner organisation Smart Fibersorting B.V., Valvan Baling Systems, Stichting Leger des Neils ReShare, Worn Again Technologies Ltd., and Procotex Corporation S.A. This project addressed two main challenges: 1) the environmental need to reduce the impact of virgin textile materials, and 2) development of new business models and open markets for the growing amounts of recyclable textiles in North-West Europe.

The Fibersort uses Near Infrared (NIR) based technology, which can automatically sort large volumes of mixed post-consumer textiles by fibre type. Once these textiles are sorted, the materials become reliable and consistent input materials for high-value textile to textile recyclers.

Near Infrared Technology

Near Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy is based on molecular absorptions and is measured in the near infrared part of the spectrum. The NIR light is selectively absorbed by fibres, creating a characteristic spectrum that is specific to the fibre. This spectrum is then compared to a predefined database, thereby making it possible to identify the material composition of the textile material.

Some advantages of using NIR technology include:

- Higher accuracy and efficiency than manual sorting as it can sort to countless predefined criteria and classifications

- Does not rely on any additional tagging of the garment

- Relatively inexpensive compared to other spectroscopic technologies.

Some disadvantages of NIR technology include:

- Darker colours and some finishes (i.e. dyes or detergents) can hinder fibre identification

- Unable to recognise low content of fibre in blends, especially elastane, which is a significant contaminant for chemical recycling

- Only able to penetrate the outermost layer of the garment.

This report showcases Phase 1 results and briefly discusses key players operating in Phase 2.

The Project was launched in May 2020 by Fashion for Good together with Circle Economy. Catalytic funding was provided by Laudes Foundation and facilitated by brand partners, adidas, BESTSELLER, and Zalando, Inditex and H&M as an external partner. Fashion for Good partners Arvind Limited, Birla Cellulose, Levi Strauss & Co., Otto and PVH Corp. are participating as part of the wider working group. Circle Economy has led the creation and implementation of the methodology, with support from TERRA, to assess the characteristics of low value textiles. Both organisations build on their extensive experience from similar projects, such as the Interreg Fibersort project30 and previous textile composition analyses.31 32 Refashion created the Refashion textiles materials library, a copy of which was used for the textile composition assessment. Matoha has provided the Near Infrared (NIR) technology, used to assess textiles composition.

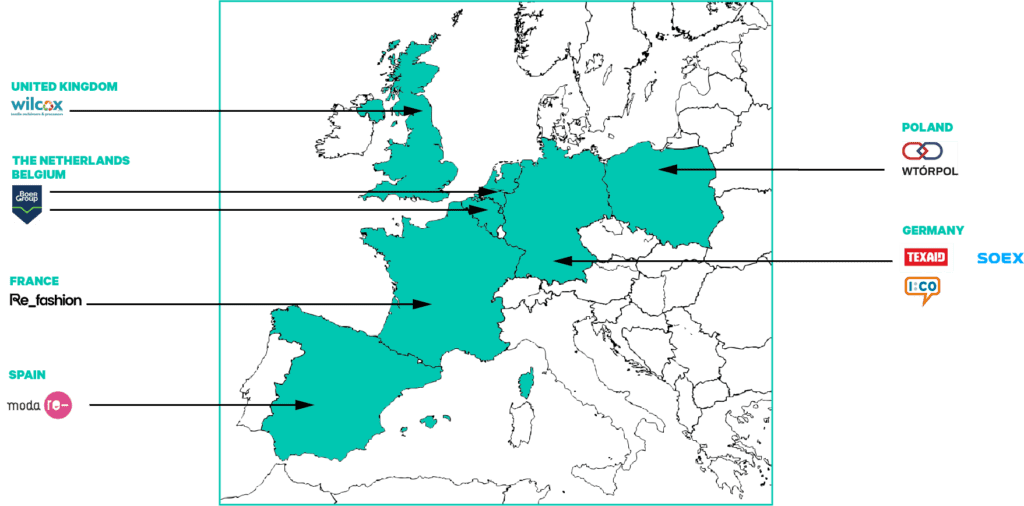

FIGURE 2. MAP OF TEXTILE SORTING FACILITIES INVOLVED IN THE STUDY. SOURCE: CIRCLE ECONOMY AND FASHION FOR GOOD (2022)

Finally, the Project brings together the largest industrial textile sorters in the North-West European region; including the Boer Group, I:CO (a part of SOEX Group), JMP Wilcox (a part of Textile Recycling International), Modare-Cáritas, Wtorpol and TEXAID (referred to as the Sorters), placing key industry players firmly at the heart of the Project and driving the industry towards greater circularity.

Sorting for Circularity is a framework conceived by Fashion for Good, with the aim to (re)capture textile waste, expedite the implementation of game changing technologies and drive circularity within the fashion value chain. – conceived by Fashion for Good together with Circle Economy. The framework is based on insights from the Fashion for Good and Aii collaborative report “Unlocking the Trillion Dollar Fashion Decarbonisation Opportunity”, which charts a trajectory for the industry to meet its net-zero ambition by 2050, highlighting the potential and significant impact on carbon emissions in the industry through material efficiency, extended and re- use of waste. Created with scalability in mind, the project was first initiated in Europe, and has expanded to include Sorting for Circularity India.

Phase 1 Scope And Approach

The project focuses on textiles that cannot be reused in their original form (considered ‘non-rewearable’) and textiles that can only be resold at low prices (‘low value rewearable’). For readability purposes, these two categories are referred to as ‘the Fraction’ solely.33 The Fraction excludes mattresses, footwear and other non-textile accessories arriving at the sorting facility. Phase 1 aimed to achieve the following objectives:

- Conduct a comprehensive composition analysis of the Fraction using NIR technology, to understand exactly what (e.g. material composition) and how much (e.g. volumes) potential feedstock for fibreto-fibre recycling is generated across European countries.

- Create a methodology that can be replicated by sorters globally and publish a handbook for sorters to implement this methodology on-the-ground.

- Map the textile recycler’s capabilities to understand how well-aligned current supply of potential feedstock is with recyclers’ processes – also illuminating potential gaps whereby greater investment and innovation must occur. This has been collected through a database of fibre-to-fibre recyclers that will be made available on the Fashion for Good website.

- Understand the future business models required for sorters to commercialise the Fraction as feedstock for fibre-to-fibre recycling.

- Reflect upon the implications of these results for the current and upcoming policy landscape in the EU.

Phase 1 followed a three-stepped approach including Preparation, Implementation and Analysis, and Reporting. A total of 21.8 tonnes of PCT have been analysed in two time periods: the first during autumn/ winter 2021, the second during spring/summer 2022, to account for seasonal changes in the types of garments entering sorting facilities. This data has been collected and analysed in a way that is comparable to the data that will be available for France through the characterisation study conducted by Refashion, commissioned to TERRA, to be released in 2023.

The following steps have been taken to analyse the sample items and form conclusions at country level:

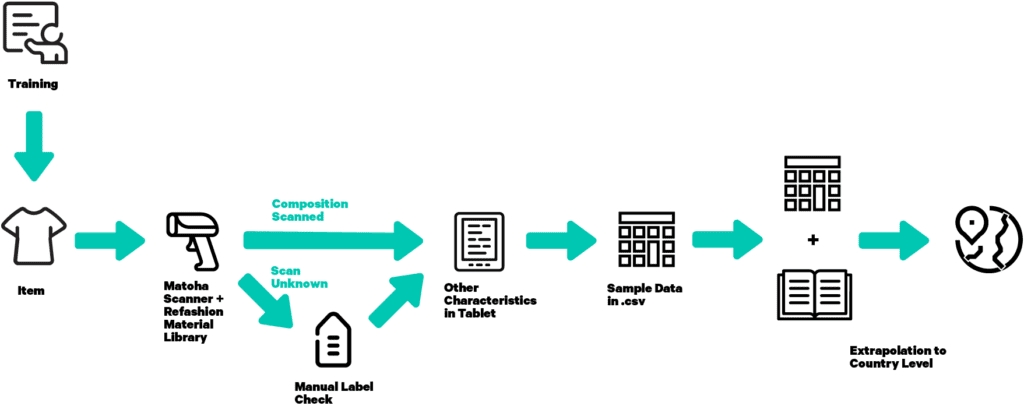

- Sorters participating in the on-the-ground composition analysis were trained in the use of the NIR device and how to track information according to the studies’ pre-defined categories (product type, presence of disruptors, etc). Training materials developed are explained in depth in the Sorters Handbook.

- Items were scanned by the Sorters using a Matoha hand-held NIR scanner which has been improved with the textiles materials library developed by Refashion to recognise fibre composition. For multilayered items, the two main layers of the garment were scanned.

- If the result of the scan was unknown, the fibre composition was manually entered using the item’s label.

- Mono vs. multi-layers, colour, presence of disruptors, product type and age group were tracked by the Sorters in a tablet device after scanning. The process of scanning the item and tracking the additional information has been conducted at an average speed of 41 seconds per item.

- The sample data was collected in .csv format.

- The sample data was extrapolated to obtain indications of volumes available in the focus countries per fibre type, using volumes from textiles collected in the focus countries available through prior literature

FIGURE 3: STEP BY STEP APPROACH FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE DEVELOPED METHODOLOGY ON-THE-GROUND. SOURCE: CIRCLE ECONOMY AND FASHION FOR GOOD (2022)

A detailed description of the activities conducted under each step of the process can be found in Annex at the end of this report.