Sorting For Circularity Europe: An Evaluation And Commercial Assessment Of Textile Waste Across Europe

The Business Case For Sorting For Circularity

Phase 1

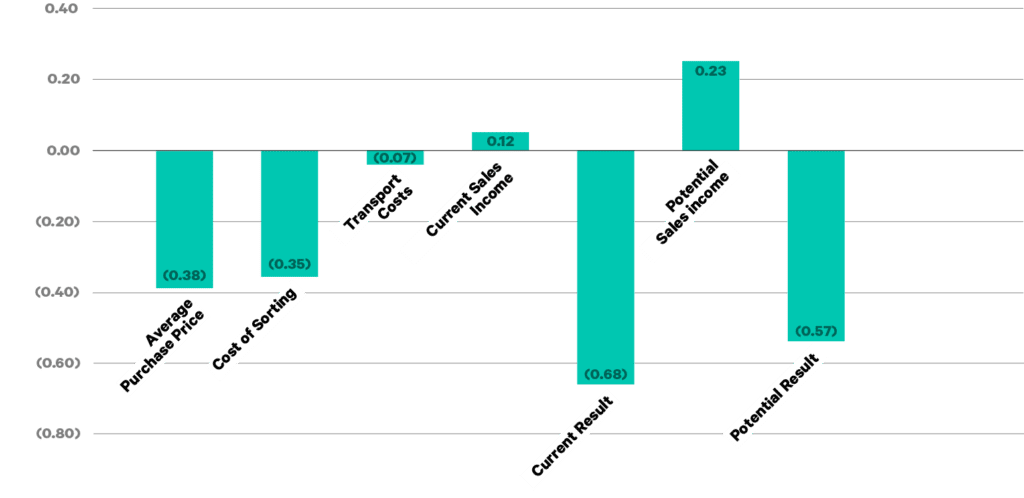

There is a common misconception that textiles that cannot be sold on second-hand markets are ‘valueless’ and could be obtained as feedstock for fibre-to-fibre recycling at little to no cost. The weighted average additional revenue generated with the Fraction (€ 0.11 per kilo) does not outweigh the costs of sorting, as illustrated in Figure 16. The negative business case for sorting these low-value materials is currently compensated by the revenue generated through rewearable textiles (as described in chapter 1). This balance will most probably no longer apply in the near future as the share of low-value textiles is projected to rise considerably as collection rates increase.71

FIGURE 16: CURRENT BUSINESS CASE FOR SORTING LOW VALUE PCT – ILLUSTRATIVE72 (PRICES IN € / KILO). SOURCE: EIGEN DRAADS AND FASHION FOR GOOD (2022)

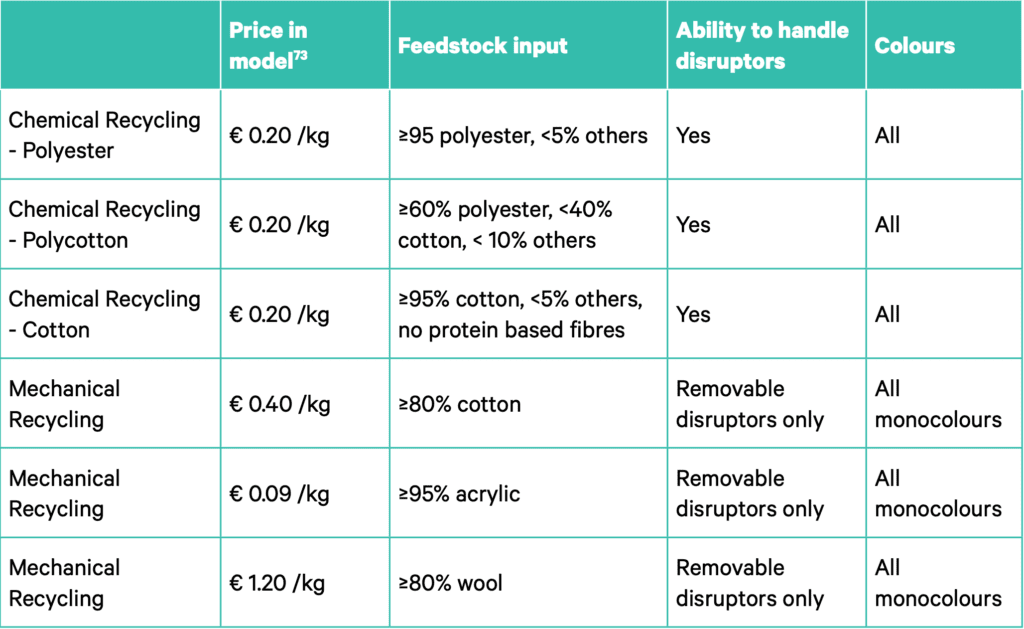

Prices paid for feedstock for fibre-to-fibre recycling will need to compete with the average sales income of sorters for these materials in order to redirect textiles from current destinations. As fibre-to-fibre recycling is not yet a mature industry at scale, prices are not yet predefined. Therefore, estimates obtained from textile sorters and recyclers were used to illustrate what the business case for sorting for circularity could potentially look like. As illustrated in Table 1, not all projected feedstock prices are competitive with current prices received (shown in Figure 5). This means parts of the volume that might technically be available as feedstock for fibre-to-fibre recycling will continue to be sent to existing destinations, like the wipers industry, in the future.

TABLE 1: BUSINESS MODEL PRICING FOR FEEDSTOCK FOR DIFFERENT RECYCLING TECHNOLOGIES AND ITS KEY REQUIREMENTS. SOURCE: EIGENDRAADS AND FASHION FOR GOOD (2022)

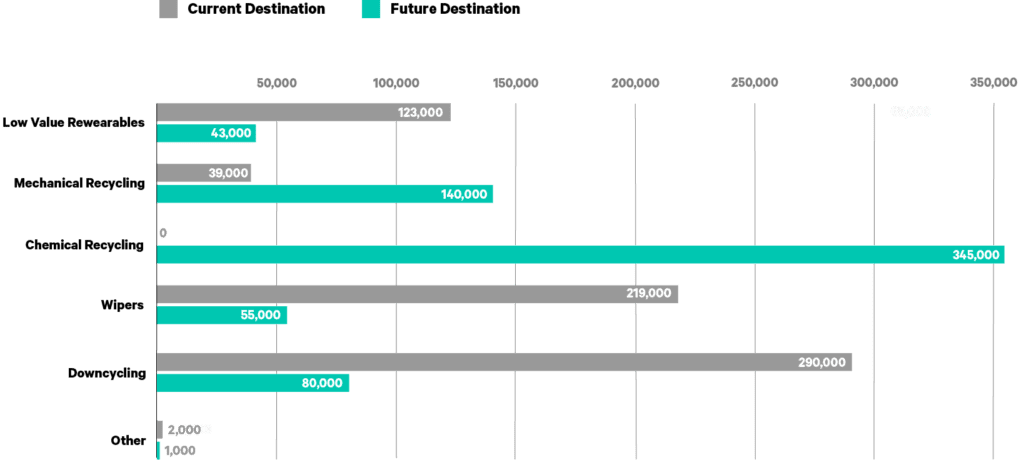

The diversion of PCT to fibre-to-fibre recycling increases the average sales income from € 0.12 per kilo in the current market to at least € 0.23 per kilo in a closed loop scenario, a net increase of € 0.11 per kilo. The total volume that could be utilised as feedstock for fibre-to-fibre recycling based on material characteristics and market value (i.e. feedstock goes to the highest bidder) in the focus countries is estimated at 494,000 tonnes per year, assuming mechanical and chemical recycling technologies are available at scale. This means that 74% of the total volume of the Fraction currently available in the focus countries could be redirected to fibre-to-fibre recycling in the future. This potential feedstock for fibreto-fibre recycling represents 23% of the total volume of textiles collected in the focus countries. In this scenario the total value created for textile sorters through sorting for circularity is € 74 million per year, for all six focus countries combined. As a result, sorting the Fraction would no longer cost € 0.68 per kilo but € 0.57 per kilo, illustrated in Figure 16.

FIGURE 17: CURRENT AND FUTURE DESTINATIONS FOR THE FRACTION IN FOCUS COUNTRIES (TONNES/YEAR). SOURCE: EIGENDRAADS AND FASHION FOR GOOD (2022)

There is an important side note to this conclusion. For textiles to be suitable as feedstock for fibre-tofibre recycling, they need to be sorted based on their composition, and disruptors need to be removed before entering mechanical recycling. In case these activities need to take place in European countries (for instance at sorters’ facilities), investments are required in technologies for automated sorting and hardware removal. This Project did not assess the business case for automated sorting of textiles nor hardware removal. A previous analysis by EigenDraads concluded that setting up a pre-processing facility with a capacity of 20,000 tonnes per year, including NIR-based automated sorting and equipment for removal of plastic and metal disruptors, would require an investment of € 5.3 million. Average costs for automated sorting and removal of disruptors are estimated at € 0.12 per kilo for the pre-processing to be financially viable. The EigenDraads study shows that the financial added value of directing PCT from their current destinations to fibre-to-fibre recyclers results in a return of investment of around 8 years, which is not realistic for private investors. A return of investment of 5 years can be realised in case a subsidy is available for the CAPEX investments of € 1.8 million. The financial added value of sorting for circularity of € 0.11 per kilo (illustrated in Figure 16) does not cover the costs for automated sorting and removal of disruptors of € 0.12 per kilo. Financial compensation through an EPR scheme is required to cover the costs associated with sorting for circularity.75 Automated sorting technologies are an addition to the current manual process in which rewearable items are separated from non-rewearable ones. There are no technologies available that could replace the categorisation of textiles based on their value for reuse on domestic and global second-hand markets. Therefore, adding automated sorting to the process will most likely not reduce the overall costs of sorting considerably.

Current global capacity of fibre-to-fibre recycling technologies is limited compared to the world’s fibre production.76 As a consequence, there is little competition between recyclers looking for feedstock. Competition amongst recyclers will increase as global recycling capacity is expected to grow considerably towards 2030.77 Considering Europe’s high collection rates, established sorting infrastructure and circular ambitions, it is well positioned to become a key feedstock supplier for fibre-to-fibre recyclers. An increased demand for feedstock for recycling will most likely drive up prices paid for sorted PCT that meet recyclers’ specifications in the future.

Textiles with a low to no value on second-hand markets have a strong negative impact on the business case for textile sorters in Europe, as illustrated in Figure 16. In a future with a surplus of textiles unsuitable for second-hand markets, the business case for textile sorting in European countries will become even less profitable. The majority of textiles collected in the European focus countries of this Project is already sorted abroad, as the sorting capacity in these countries only accounts for 43% of the volumes of textiles collected. Increasing shares of low-value textiles in combination with current shortage on the labour market (and consequent pressure on minimal wages in European countries) might incentivise textile sorters to move (a part of) their activities to lower income countries in the near future. The introduction of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) regulation, discussed in more detail in the next chapter, could alleviate the burden caused by decreasing value of textiles sorted and high labour costs in European countries, if the financial support provided to sorters covers the future costs of sorting textiles. An exploratory study in the Netherlands concludes the financial support projected to be available for sorters through the upcoming EPR scheme as € 0.20 per kilo. This unfortunately will not cover the future additional costs of sorting, estimated at € 0.27 per kilo.78 Therefore, the increase in prices paid for feedstock for recycling, due to increased demand, will be essential in combination with legislation such as mandatory EPR schemes, to sustain the business case for sorting in Europe.