Unlocking the Trillion-Dollar Fashion Decarbonisation Opportunity

The Role of Finance in Decarbonising The Fashion Supply Chain

The Role of Finance in Decarbonising The Fashion Supply Chain

“When it comes to a complete change in energy use or a new way of manufacturing, the manufacturer cannot take on the entire cost burden and project risk. There needs to be additional stakeholders to co-invest alongside the manufacturer to implement disruptive and sustainable technologies.” – Punit Lalbhai, Executive Director, Arvind Limited

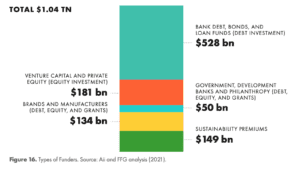

TYPES OF FUNDERS

This report has identified five different funder types that will each play a role in financing the $1 trillion decarbonisation opportunity:

BANK DEBT, BONDS, AND LOAN FUNDS (DEBT INVESTMENT)

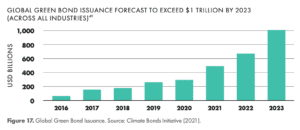

Bank debt includes loans from local, regional, and international banks. Bonds are primarily publicly traded instruments issued by banks, brands, or manufacturers. Loan funds are private investment funds that make loans directly to companies and projects. Debt capital typically invests in lower risk projects with a high degree of certainty. Embedding sustainability aspects in debt financing has become quite widespread as seen in Figure 17 below.

H&M GROUP’S SUSTAINABILITY-LINKED BOND TO SCALE RECYCLED MATERIALS50

Sustainability-linked bonds are something new on the bond market. In contrast to green bonds, where the funds are linked to specific projects, sustainability-linked bonds are coupled to the company meeting a number of defined sustainability targets.

H&M sustainability-linked bond raised EUR 500 million ($583 million) with a maturity of 8.5 years. The annual coupon rate is 0.25%. The bond generated great interest and was 7.6 times oversubscribed.

The targets* that H&M Group has committed

to achieving by 2025 are:

- Increase the share of recycled materials used to 30%.

- Reduce emissions from the Group’s own operations by 20%.

- Reduce absolute Scope 3 emissions from fabric production, garment manufacturing, raw materials and upstream transport by 10%.

*For more detailed information see

H&M Group Sustainability-Linked Bond Framework.

“For H&M Group, sustainability is an integral part of our operations. This type of bond creates a clear and transparent commitment and incentive for the company. It is an important step in our continued work to optimise the company’s capital structure, while at the same time providing investors with an opportunity to contribute to the positive transformation of the fashion industry.”

ADAM KARLSSON, CFO, H&M GROUP

THE GOOD FASHION FUND51

The Good Fashion Fund is a one-of-its kind initiative to create systemic change in the textile and apparel industry by making loans to finance the implementation of highly impactful and disruptive production technologies in Asia.

The capital structure of the Good Fashion Fund is a blended finance structure comprising 3 different risk/return layers: Junior Equity /first loss, Senior Equity, and Senior Debt tranche.

The fund has been active since the end of 2019, has a target size of $60m and its typical investments are between $1m and 5m. It finances apparel manufacturers in India, Bangladesh and Vietnam for adoption and implementation of impactful technologies. This kind of long-term USD financing is barely available for manufacturers that are keen to become more sustainable but do not have their own funds or bank loans available to finance this.

The first deal of the fund was a $4.5m loan to support Pratibha Syntex’s planned capital expenditures for the replacement of machinery and expansion of sustainable equipment in their spinning, processing and garmenting divisions. The company supplies textiles and garments to popular brands including C&A, H&M, Patagonia and Zara.

Although the fund itself is too small to enable systemic change, the fund hopes to demonstrate that investing in the sustainability investments of smaller manufacturers leads to healthy financial returns, and therefore can be done at scale by existing financial institutions.

VENTURE CAPITAL AND PRIVATE EQUITY (EQUITY INVESTMENT)

Venture capital and private equity make equity investments directly into companies and low-carbon projects. This type of capital is seeking higher return investment opportunities and consequently accepting higher risk.

CASE STUDY: JEANOLOGIA52

Jeanologia’s laser technology is applied to 20% – 30% of the billions of jeans manufactured annually, allowing for an increase in productivity, reduction of water and energy consumption, while eliminating waste and harmful emissions. The innovator was founded in Spain in 1994, but has gone on to become a dominant equipment provider for modern denim production, selling its equipment to manufacturers in about 50 countries.

In 2019, private equity group Carlyle led a EUR 60 million ($70m) equity financing transaction, and Jeanologia secured an Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance (ESG) linked term loan later that year, with costs tied to water-saving targets. Interest rates on the loan decrease if Jeanologia meets those goals, and go up if the company misses its targets by 15% or more.

BRANDS AND MANUFACTURERS (DEBT, EQUITY, AND GRANTS)

Brand and manufacturer capital represent corporate treasury dollars or support that come from within a company’s budget directly. Many of the projects in this report include brand and manufacturer dollars to assess feasibility or support low-carbon projects by co-investing alongside financial capital.

Given the fashion industry’s specific supply chain interdependencies between brands and their Tier 1 suppliers, brands may act as a facilitator and multiplicator for low-carbon finance granted to their suppliers. The following case studies show examples of brands facilitating low-carbon finance for their suppliers:

PUMA AND ITS INSURER PROVIDE ESG-LINKED INSURANCE PREMIUMS FOR THEIR TIER 1 SUPPLIERS

The approach to offer preferential rates for Tier 1 suppliers with above average ESG rating also works for non-financing products like insurance. PUMA is arranging liability and recall insurance for their Tier 1 suppliers that either have no access to similar insurance coverages or suffer much higher premiums on a stand-alone policy. Through this programme, suppliers with better ESG ratings pay lower insurance premiums.

“With this programme, we can leverage

our economies of scale with the Insurer and let our suppliers directly participate from lower premiums. For the insurance company, better ESG ratings are connected with better production conditions for the workers in the supplier’s factories, less product issues with the finished goods and consequently lower claim numbers. We consider this as a Win-Win-Win situation.”

FRANK WAECHTER, GLOBAL DIRECTOR TREASURY & INSURANCE, PUMA SE

LEVI STRAUSS & CO. AND IFC PROVIDE LOWER COST SUPPLY CHAIN FINANCING FOR MANUFACTURERS THAT IMPLEMENT ENERGY EFFICIENCY MEASURES53

Under a new partnership between Levi Strauss & Co. and the International Finance Corporation (IFC), facilities that participate in the PaCT programme (for more detail, see ‘Partnership for Cleaner Textiles (PaCT)’ on pg. 19), have access to larger loans and lower cost financing through IFC’s Global Trade Supplier Finance (GTSF) programme, which offers low-cost capital and early payments on completed orders to suppliers that meet environmental and social standards. This type of financing has been welcomed by suppliers and the programme has already increased the amount of financing available to meet the growing need.

“The fundamental driver is that these investments make economic sense. We identify cost-effective water and energy savings and renewable energy solutions to these suppliers. These are climate-friendly investments that make economic and environmental sense and, on a life-cycle cost basis, these are highly attractive investments that are paid off in one to six years with increased savings.”

JEREMY LEVIN, SENIOR ENERGY SPECIALIST, INTERNATIONAL FINANCE CORPORATION

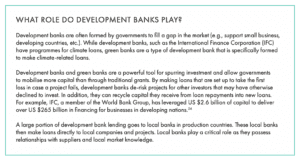

GOVERNMENT, DEVELOPMENT BANKS AND PHILANTHROPY (DEBT, EQUITY, AND GRANTS)

Government, Development Bank and Philanthropy investments seek to promote a sustainability goal for society. Investments may consist of direct equity investments, grants, interest free / subsidised loans, loan guarantees, or other economic incentives (e.g., feed-in tariffs). This type of capital is important for de-risking early-stage technologies and helping them reach scale.

SUSTAINABILITY PREMIUMS

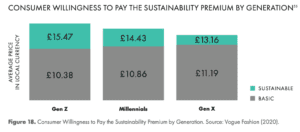

A sustainability premium is an increase in cost resulting from the implementation of sustainable materials or services, that may be either temporary (e.g. because new materials or processes are not yet at scale) or structural (e.g. paying higher wages in the supply chain). This additional cost must be funded by a stakeholder in the value chain (customer, brand, government etc.), otherwise the project will not move forward. Figure 18 shows that consumers, especially of younger generations, are willing to pay more for a sustainable product. While this could fund part of the sustainability premium costs, it should be noted that there is also a discrepancy between how people say they’ll spend their money versus how they do in practice.

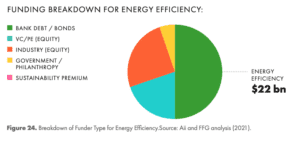

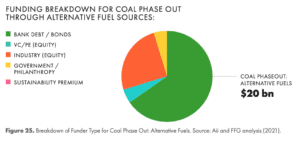

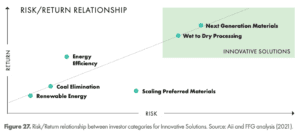

BREAKING DOWN THE SIZE OF THE PRIZE BY TYPE OF FUNDER

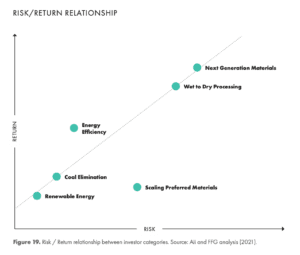

Each of the solutions offered in this report will attract a different range of investor categories, driven by differences in (perceived) risk levels, as shown on the risk versus return graph in Figure 19:

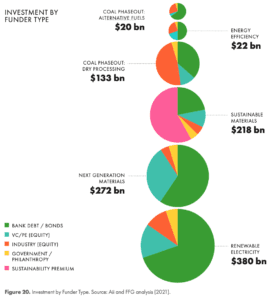

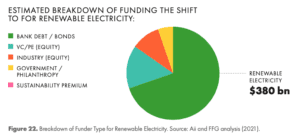

In most cases, multiple types of financing will be involved in a single project. Projects with higher risk will typically have a higher percentage of equity capital, whereas projects with lower risk will have a higher percentage of debt capital. However, nearly all projects will include a mix of both debt and equity capital. Figure 20 shows a breakdown of the types of funders for each solution:

The following section deep-dives into each of the solutions to break down the funding required by funder, and provides examples of existing initiatives to demonstrate the opportunity within.

THE ROLE OF FINANCE IN EXISTING SOLUTIONS

“We have found many smaller manufacturers struggling to attract debt financing for interesting and impactful projects despite sufficiently strong financial performance” – BOB ASSENBERG, GOOD FASHION FUND

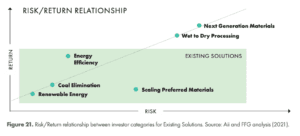

Existing solutions have a lower risk profile and therefore attract a different type of financing mix than innovative solutions.

Qualities of projects with a lower perceived risk profile can include:

- Financing of a proven investment that has been done many times before, e.g. installation of solar panels on the roof of a factory — the technology itself has been proven to be feasible thus no technology risk

- Contractual agreements that give a higher certainty of project cash flows, e.g. long-term contracts

- Financing of hard assets that have a relatively high value for alternative uses, e.g. leasing equipment that can be readily deployed in other facilities

Why is Financing Needed?

Although implementation of low-carbon equipment in factories often has a compelling investment case, (local) debt financing is not always widely available. Manufacturers often operate at thin margins and may lack the financial strength to attract debt financiers for sustainable projects. Even the most financially strong manufacturers are not able to fully fund projects themselves.

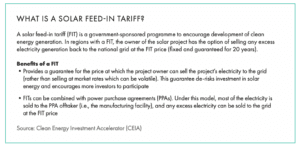

Funding the shift to 100% renewable electricity

Of all the solutions discussed in this report, renewable electricity is the most proven solution with the lowest overall risk profile, and can therefore be funded with a high percentage of debt financing in most markets. Renewable electricity is typically low risk because generation technologies, such as solar and wind have been proven to work around the world. Furthermore, electricity prices are relatively stable, so most projects have a known payback period. Government incentives, such as feed-in tariffs, can help de-risk projects even further, and make certain projects fundable that may have otherwise not been viable (e.g., a project in a region with only a moderate amount of sunlight).

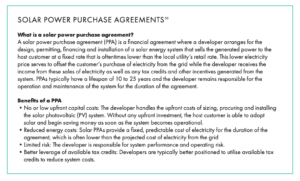

ON-SITE RENEWABLE ELECTRICITY FINANCING CASE STUDY57/58

Project Overview

In 2021, Berkeley Energy Commercial Industrial Solutions (BECIS), a solar developer, installed 8 megawatts (MW) of rooftop solar at two textile facilities owned by Hansoll Textile in Vietnam. The total cost of the project was $5.6mm (~$700 per kW), which was funded entirely by the solar development company, an example of private equity financing. The two textile facilities signed 15-year power purchase agreements (PPA) at a discounted rate to their electricity cost from the local utility (~$135,000 in savings for the manufacturers per year).

Strategies Used to Increase Project Viability

- The systems were designed to meet the electricity needs of the facilities, which reduced reliance on selling excess electricity back to the grid

- By combining the two facilities into one project, the total system size increased to 8 MW and created cost efficiencies

- The project took advantage of Vietnam’s zero import duty on solar products CO2eq savings: 10,000 tonnes per year

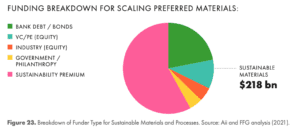

Scale Sustainable Materials and Processes

There are two main categories of financing for scaling sustainable materials and processes —

(i) infrastructure investment for collecting input materials and converting them into fibres

(ii) the sustainability premium (i.e., the cost difference between sustainable materials and conventional materials).

The infrastructure investment is asset heavy and positive ROI, and can therefore be funded with debt and equity.

The sustainability premium is primarily a cost, with limited financial ROI. However, some brands have been able to achieve some financial benefit by effectively marketing their use of sustainable materials. Ideally, customers would be motivated to bear most of the sustainability premium in the form of higher retail prices, but in the absence of regulation that requires sustainable materials, some portion of the sustainability premium will likely need to be funded by brands, philanthropic dollars, government funds, and potentially concessionary financing.59

Maximise energy efficiency

Given the high return on investment and relatively short payback period, many energy efficiency investments are funded by the manufacturers themselves, which is reflected in the higher percentage of manufacturer funding in the investment breakdown by funder type. Nevertheless, it can be difficult for manufacturers, even those that are large and well-established, to find enough capital to make these investments themselves, so banks and equity investors have an important role in filling the gap. Given the small size of these investments, there is a need for aggregation of projects in order to attract deeper pools of capital. In addition, manufacturers are hesitant to take on additional debt for projects like these due to the risk that cost savings may not materialise and/or brand order volumes may decline. Equity investment is a potential solution as the downside risk is shared between investors and manufacturers. Finally, brand guarantees and volume commitments would further reduce risk for manufacturers and investors.

CLEAN BY DESIGN DEMONSTRATES AN ATTRACTIVE ROI FROM ENERGY EFFICIENCY INVESTMENTS61

The Clean by Design programme helps manufacturers identify manufacturing efficiency improvements to reduce energy, water and chemicals use (See ‘Clean by Design Highlight’ on pg. 20). The programme has proven to be effective at achieving sustainability goals as well as generating a strong ROI for manufacturers.

SOME HIGHLIGHTS OF THE PROGRAMME INCLUDE:

- Average GHG reduction: 10.8%

- Average annual energy cost saving: USD $369.5k (12.6% reduction)

- Average payback period: 13.8 months (60%+ ROI)

To date, the majority of energy efficiency investments in the apparel industry have been funded by a mix of manufacturer equity and bank loans. However, given the high ROI of the program, the authors see an opportunity for private equity investment to increase adoption.

Phase Out Coal with Alternative Fuel Sources

Coal boilers typically have a long life (10+ years). The ROI for a coal replacement project varies significantly depending on whether the project is replacing a coal boiler during its useful life or at the end of its useful life. Therefore, it is key that all planned new boiler installations switch to an alternative fuel source. Given that these projects typically have a positive ROI, consistent cash flow profile, and are backed by the boiler as an asset, debt financing is the primary source of funding. However, as showcased in the below case studies, there are innovative methods for funding the transition from coal that go beyond traditional bank loans.

SKYVEN TECHNOLOGIES’ ENERGY-AS-A-SERVICE FOR PROCESS HEAT62

Outside of the apparel sector, Skyven Technologies has pioneered an innovative approach to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in industrial manufacturing. Many thermal energy related capital projects (e.g. boilers, industrial heat pumps, recuperators, etc.) have payback periods longer than two years, making them difficult to get through a typical capital-approval process. Skyven offers to cover upfront all capital costs and maintenance costs related to implementing such projects.

Using a state-of-the-art, proprietary Internet of Things (IoT) technology to measure and verify the energy savings generated by such projects, Skyven can bill for the saved energy at a discount from what the facility would have otherwise paid for that energy. This unique model allows manufacturers to reduce emissions with zero CapEx, reduced risk, and savings from day one. While this structure is not currently being used in the fashion industry, this type of financing could be replicated to mobilise finance in the fashion industry.

THE ROLE OF FINANCE IN INNOVATIVE SOLUTIONS

Characteristics of the Financing Innovations

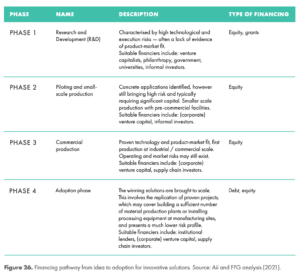

Whereas existing solutions can be implemented immediately, innovative solutions require further development before they can be implemented at scale. Therefore, the first three phases below are relevant when discussing the funding paths innovative solutions must follow:

Phases 1 through 3 are financed by equity only as a result of the significantly higher risk profiles compared with Phase 4 and the existing solutions described previously. The higher risk profiles are the result of one or a combination of the following factors:

- the presence of technology risk; often up to and including Phase 3,

- the lack of attractive unit economics; which will only be reached at industrial scale,

- low revenue

- negative cash flows

Importantly, before Phase 4, there is no significant role for debt funding. Once Phase 4 is achieved and growth is merely about replication of a proven, commercially successful, set-up, debt financing becomes available and a further roll-out can be implemented at an accelerated pace.

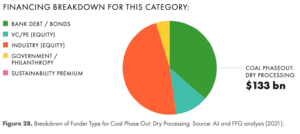

Coal Phase Out: Dry Processing

About 10% of the financing requirements in this category relate to Phases 1 through 3 capital, with the remainder needed for implementation and further adoption of the developed solutions.

Taking into account geographic dynamics and the often limited debt capacity of manufacturers, a degree of asset-based lending is possible for manufacturers in Phase 4; this analysis assumes 40% of debt coming from lenders in this phase. On an aggregated basis, that means 59% is coming from equity sources, either from the industry (manufacturers) or new equity funders including private equity and venture capital.

CASE STUDY: SCALING ALCHEMIE TECHNOLOGIES

Alchemie Technology has developed clean-tech dyeing and finishing processes which are enabled by its unique digital fluid jetting technology. Alchemie’s digital manufacturing solutions for dyeing and finishing deliver significant reductions in environmental impact: reducing wastewater, chemistry and energy consumption.

Earlier this year, Alchemie’s first large funding round attracted investments from H&M CO:LAB and At One Ventures63 to accelerate development and implementation of its disruptive equipment and technology.

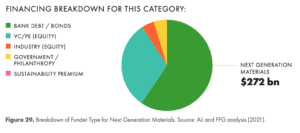

Next Generation Materials

In contrast to Wet to Dry Processing, Next Generation Materials requires production plants to be built to produce materials at scale. Therefore only 8% of the financing requirements in this category relate to Phase 1 through 3 capital, with the remainder being Phase 4. Given that Phase 4 has been defined as the replication of projects that have already been completed in the past, it can safely be assumed these projects carry significantly less risk. For some innovators, the potential existence of long-term offtake agreements and/or a predictable and transparent product market will support a case for debt financing. In Phase 4, innovators can be optimistic of their leverage in rolling out new materials plants, as evidenced by the financing structures of current comparable facilities of listed commodity producers (e.g. PET, viscose, specialty chemicals). As a result, it is assumed debt financing of these projects may average 65% in Phase 4. On an aggregated basis, this results in 60% of the financing requirements being debt capital.

CASE STUDY: RENEWCELL AND EUROPEAN INVESTMENT BANK64

In June 2021, the European Investment Bank (EIB) signed a loan agreement of EUR 30 million ($35m) with the circular materials innovator Renewcell in Sweden, under the InnovFin “EU Finance for Innovators” programme that launched in 2014 within the EU Horizon 2020 programme — the EU’s programme for research and innovation.

The Sweden-based innovator has devised a way to turn discarded textiles into “Circulose”, their brand name for the pulp from which new fabric can be made, thus boosting the circular economy as a concept in the fashion industry. Renewcell will use the EIB loan to build their first full commercial-scale textile recycling plant in Sweden, able to produce 60,000 tonnes of fibre annually.

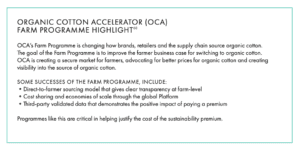

Scaling Next Generation Materials: a Note on Sustainability Premiums

Given the current low-output volumes and therefore absence of process optimisation and economies of scale, it is currently unknown whether new materials will be able to reach competitive price points. In the absence of significant regulation, sustainability premiums may hinder next generation materials in penetrating the market in a globally significant way. However, given that the prices of some materials (e.g. polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) and Polylactic acid (PLA)) have been decreasing in recent years, paired with the increasing availability of low-cost feedstock for many innovators, there are reasons to believe competitive pricing will be achieved.

Additionally, for many new and recycled materials, a transitory period exists in which prices are not competitive with conventional materials until reaching production at an industrial scale. In the absence of governments or philanthropies stepping in to finance these temporary premiums, brands and/or manufacturers would have to pay premiums for new fibres that, in many cases, are priced significantly higher compared to current alternatives. While brands have been able to achieve some financial benefit by effectively marketing their use of sustainable materials and charging higher prices, this presents a challenge to scaling and achieving the potential impact of these innovative materials.